In response to the closure of live theatre across the country, we explore the history of theatrical entertainment in Horsham, in a dramatic retelling of the story.

Every good play starts with a title, in this case “The Dramatic Tale of Horsham Theatre”. The programme usually has a list of characters with the lead actor taking the headline spot. For this tale that headline role would belong to Sir Michael Caine (though at the time we are discussing he was actually a bit part actor at the very start of his career). Next, we have the prologue, and multiple acts (usually three). Our performance is not your average comedy, but a historical play that involves attempted murder, soldiers, drama and a good dose of mystery.

Act One – The Case of the Missing Theatre

On Twelfth Night 1823 posters appeared on buildings around town telling the residents of the Horsham that the bailiffs and burgesses had allowed a performance of She Stoops to Conquer to be performed at The New Theatre, Horsham. To have a New Theatre we must have an old one. But where was the Old Theatre? That is the mystery!

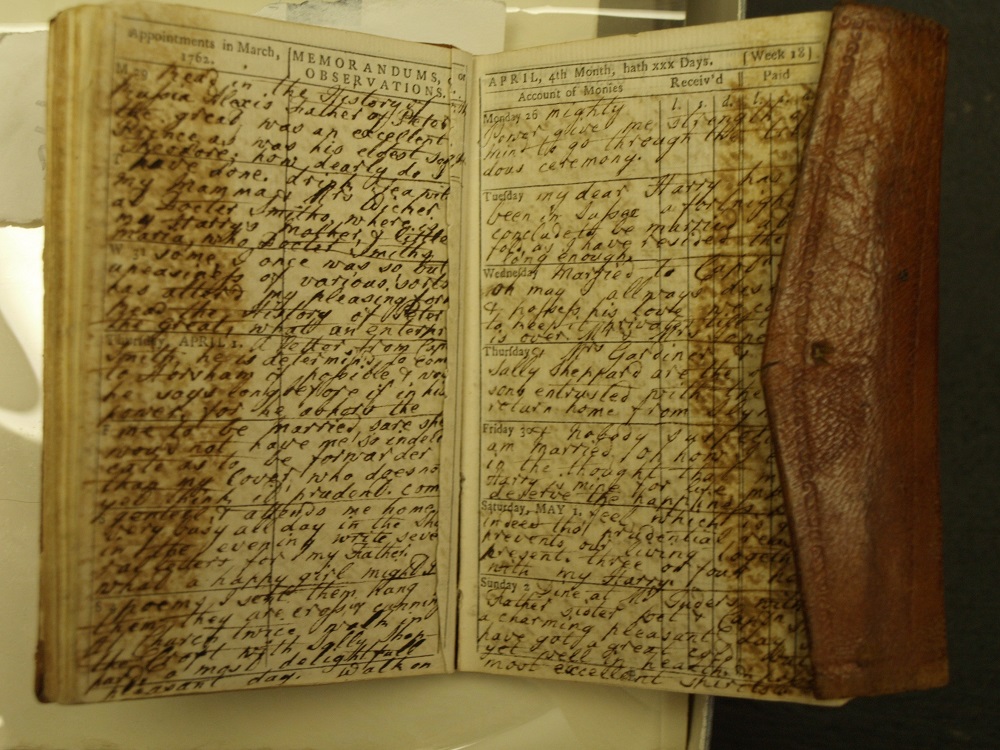

Until the publication of the 18th century businesswoman, Sarah Hurst’s, diaries in 2003 we didn’t know anything about the earliest plays performed in Horsham. Sarah’s diaries record that she saw 5 plays in Horsham in 1759, six in 1761 and two in 1762. She also saw a number of plays when visiting London, including two performed by the greatest actor of his age, Garrick. Sarah’s comments in her diary suggest that seeing plays in Horsham was not regarded as a novelty, but part of everyday life. This in turn suggests theatrical performances must have been performed in the town before 1759. On Monday 30 April 1759 Sarah’s diary records:

The players act The Fair Penitents, have a tolerable house & they say did it pretty well & glad on’t, t’s a sad thing not to succeed.

Not only is there no excitement in the diary, no effusiveness regarding the players’ arrival in town, but also when on the 26 June she records “go & see The Busy Body, last time of our players performing”, there is every expectation of a return with no comment on the loss. Her reference to “our Players” - suggests they were either itinerant performers resident in the town for so long as to be seen as part of Horsham society, or perhaps, based in Horsham but touring other towns in the summer season.

Some 10 years later the diary of local man, John Baker, records him seeing a play on 10 July 1772 that included “Some rope dancing, singing and “Midas” and Harlequin Skeleton”. What makes the account interesting is that Mr Baker records in the diary in French, a deliberate comment about Mr Shelley and his “duchess”, thus making the spectators the spectated and highlighting the role of the playhouse as a space in which to watch and to be watched.

The comments made by the impresario Charles Osborne, who had his own troop of actors, show what the good folk of Horsham really wanted. He wrote in 1785 that:

I intended to have…the Town Hall as a Theatre tomorrow, but the arbitrary oppressive manner, as well as the violent threats that have been made….induced me to decline my intentions instead, I propose to open an Histrionic Academy for three nights only…”, which suggests that there was not a market in Horsham for actual theatre, more for “burlesque”

At the time of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, if you wanted to perform theatrical performances, you had to ask permission of both the town management and the local military commander. The Museum has a few examples of such requests, yet none identify a theatre.

An Interlude - Drama in Court

At the 1801 Easter Assizes, held at Midhurst, the court heard a drama worthy of a theatrical production. It involved a lover, an actress and an infatuated ensign. The lover was George Stanton, a part-time actor. The actress was Mrs Leach, “a lady possessed of Youth and a Handsome person and not destitute of Dramatic Talents, but like many of her sex on the stage fickle”. Mr Stanton fell in love with Mrs Leach, though when he proposed marriage, she only wanted friendship.

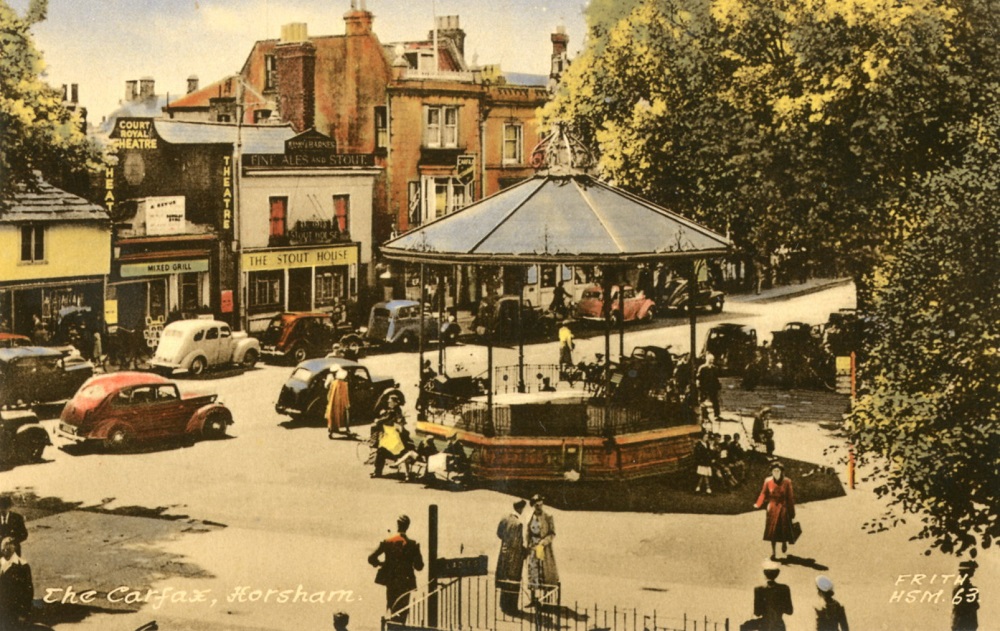

The ensign, William Bunn, who was stationed at Horsham Barracks with the 64th Regiment, also fell violently in love with Mrs Leach. On 21 December 1800 William Bunn attempted to murder George Stanton, with a pistol in each hand, in the Carfax at around midnight. Bunn only grazed Stanton but, thinking he had killed him, he fled. The morning after, having realised that Stanton was only injured, Bunn and Mrs Leach told the magistrate that Stanton had in fact attacked Bunn. Stanton was arrested prior to a trial at Chichester.

At Chichester neither William Bunn nor Mrs Leach turned up for Stanton’s trial. Stanton then filed an assault case against Bunn. Bunn was eventually captured on board a ship in Portsmouth Harbour under a hen coop. Stanton later told the court that he would not prosecute Bunn if Bunn agreed to pay his expenses. The jury, realising the nature of the case, declared Bunn not guilty. We have since found out that Bunn did eventually agree to pay Stanton’s fees.

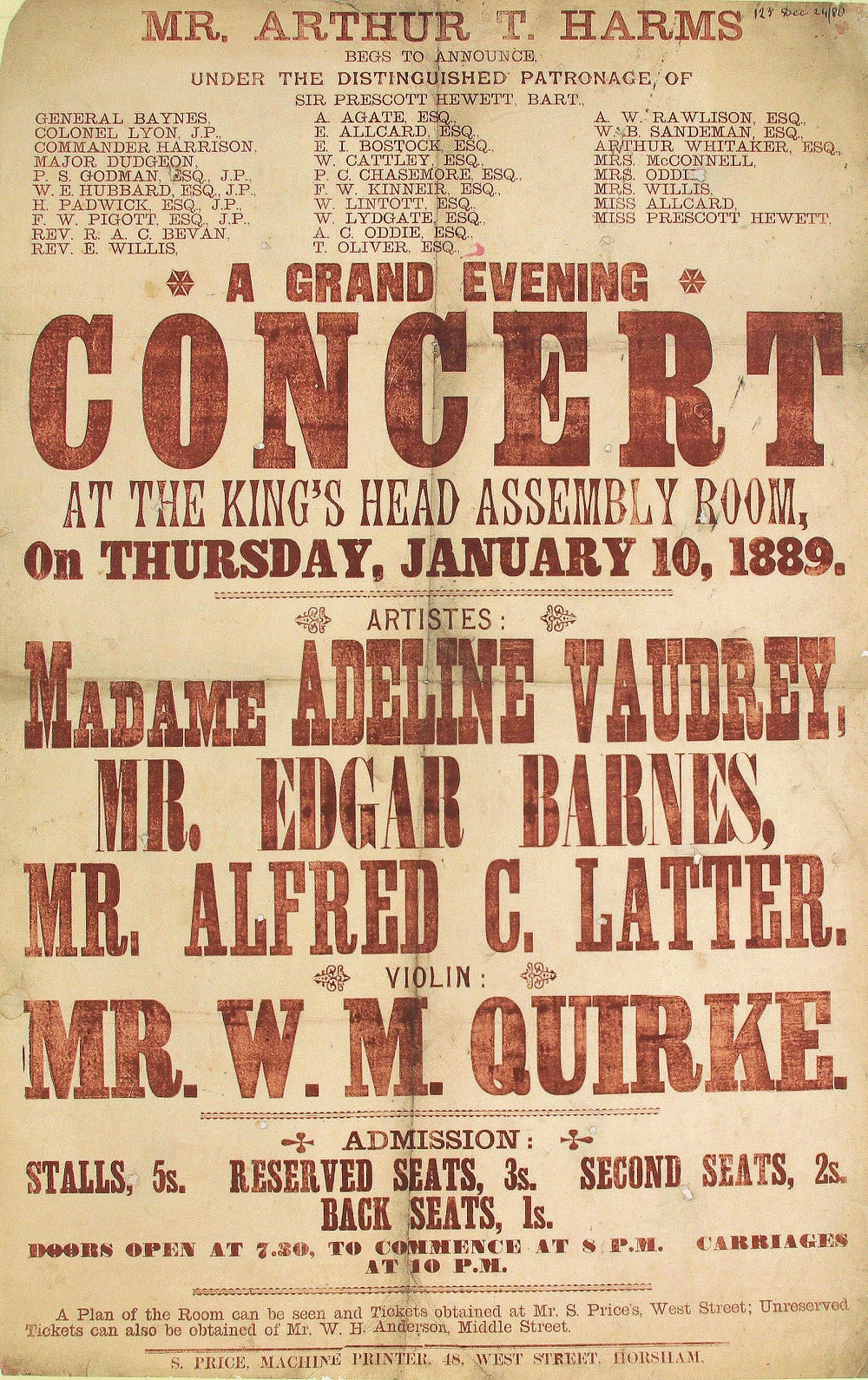

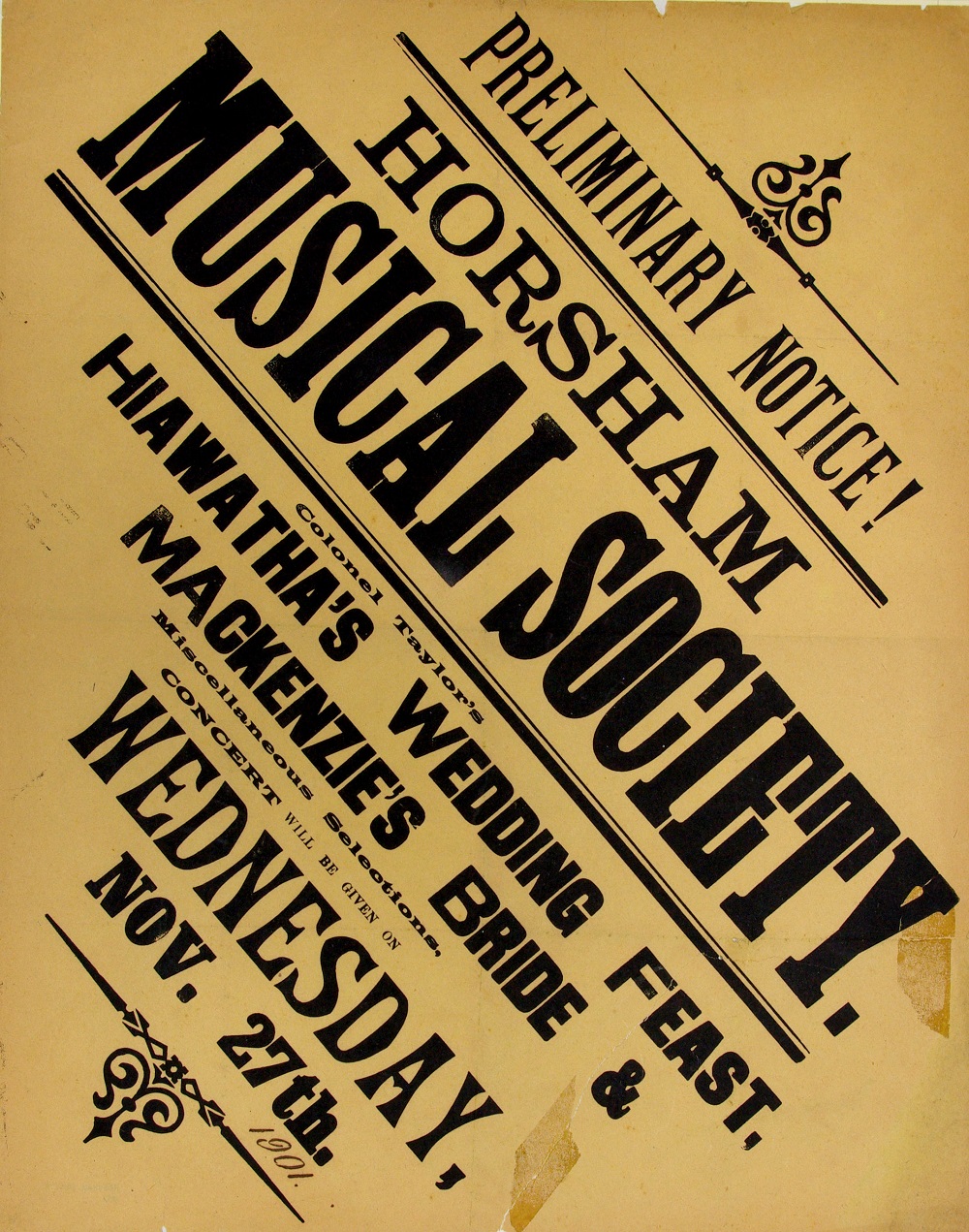

Act Two – Assembly Rooms Rather Than Theatres

Throughout the 19th century Horsham seems to have had no actual theatre. There were theatrical performances, held in pubs and inns, and the town was blessed with two large assembly rooms; the Kings Head and Richmond Hotel. When the Corn Exchange was built in the late 1850s it was intended to be used as a meeting room and, being next to the Black Horse Inn, it also took on the function of an assembly room. The posters from the period show that many performances took place in town, and a comment in 1868 Horsham Journal shows that amateur dramatics had a strong following:

A respected correspondent has drawn our attention to the fact that during the recent July fair the Volunteer Fire Brigade Band (in uniform) performed at a travelling “Theatre” which our correspondent thinks they would not have done had they manifested a due regard for their own respectability, or for the known wishes of some of their kindest patrons Upon that matter we do not desire to express an opinion, but it may be remarked by the way that the true old saying, “You may know a man by the company he keeps, “ applies as fully and as forcibly to Volunteer Fire Brigade Bands as it does to private individuals.

This remained the case into the Edwardian era, a heyday for the London theatre. In 1912, The Daily News and Leader published an article titled “Our Mirthless village” by E. Clapham Palmer, supposedly a correspondent who knew Horsham:

Sir- So London spends a £30,000 a day on being amused…. In little country towns and villages it is necessary to live without being amused. In a place like Horsham of 12,000 inhabitants, there is little chance of being entertained unless the cricket club, or the football club, or some other deserving institution, is good enough to get into debt. Then, perhaps, someone will get up amateur theatricals, and give us an entertaining evening.

The article goes on to say that once a month during the winter a touring company would put a show on in the assembly room of the chief hotel, probably the King’s Head, and noted that despite plans to build a larger hall, the construction of a proper theatre venue never came to fruition. However, what is clear from all the posters in the museum’s collection, the people of Horsham preferred variety shows to plays, despite the lack of a Music Hall.

Act Three – The Theatre Electric Arrives

The biggest change in Horsham’s theatrical scene came with the arrival of the cinema. Without the investment from, and popularity of film, it is doubtful whether Horsham would ever have had a stage on which to perform. The economics haven’t changed 100 years on, as Mr Palmer wrote in 1912:

“We have, of cause, the cinematograph, and we are very grateful for it. We have even a uniformed doorkeeper, who stands outside the corrugated iron picture theatre and gives the place, with the assistance of dazzling lights overhead, almost a London air. The fact that we can support two picture theatres shows that we are anxious enough to be entertained.”

The following story only later gains importance as it is the place where future “Knight of the Stage and Screen”, Sir Michael Caine, would make his mark. In October 1911 The Carfax Electric Theatre opened. The entrance was through the alley at the side of the Stout House, and it had a small sign suspended over the pavement. Plans for a 40ft long hall were submitted in June 1911 by the brewers, King and Barnes, but instead, the cinema was established by brothers Philip and Charles Bingham. In 1917 the Carfax Electric Theatre purchased 28 Carfax, Walter Oldershaw’s outfitters shop, which was next to the pub and directly in front of the auditorium. This building was then converted into an entrance. This and other improvements saw the theatre renamed to Carfax Theatre with a grand opening by the famous writer, Hillaire Belloc.

The 1920s saw the creation of the Horsham Players, an Amateur Dramatic organization. As Signpost, the shopping magazine, reported in 1926:

A dramatic Society known as The Horsham Players has recently been formed in Horsham. In every community there is a need for the best drama; and, hitherto, Horsham has lacked any united and steady effort to supplement the films. Mr. Pomroy Sainsbury the President, Mr. Horace T Knott, manager of Barclays Bank, is Hon Treasurer, Miss K Hussy is Hon. Secretary. Other committee members are Mr. Hamilton Fyfe Headmaster of Christ’s Hospital, Rev. C. T. Parkinson Master of Christ’s Hospital, Mr. Ernest Bertram a veteran professional actor, Mr. R. T. Sharpe barrister, Mrs. Pomroy Sainsbury, Mr. Bertram whose son is the art critic Mr. Anthony Bertram, was closely associated with Sir H. B. Tree and Sir George Alexander in many of their London successes, acting in “Trilby” and the lead in “The New Sub” which had a 200 nights at the Court Theatre.

Then in 1929 Horsham’s entertainment world saw the biggest change of all, the town finally had its first permanent, purpose built, theatre. In autumn 1929 the Blue Flash Company owned all three cinemas in the town; Central Hall, Carfax and its finest, The Capitol. That October, at The Capitol, the company installed sound apparatus so it could play talkies. The purpose of The Blue Flash Company was to provide employment for out of work bandsmen who had previously been in the army. The bandsmen would then use their musical skills to play live soundtracks for the silent shows. Now that talkies were being shown, and demanded by the public, the need for live music rapidly declined. The Carfax cinema therefore decided to close for a week and convert its space into a live theatre. They held a season of plays by Frank Buckley’s Repertory Company, realizing that it would be difficult for silent films now to compete with the talkies.

Act Four – A Knight Begins as a Knave

Post-war Horsham saw a notable entrant onto its stage – Michael Caine - whose acting career began in the town. Caine responded to an advertisement for an Assistant Stage Manager at the Horsham-based Westminster Repertory Company. This position led to walk-on roles at the Carfax Theatre where he worked for 9 months. Sadly the company closed whilst he was sick with malaria, an illness he picked up in Korea during military service.

The other development in the 1950s was the formation of HAODS (Horsham Amateur Operatic and Dramatic Society), who started off by primarily performing works by Gilbert and Sullivan. They performed in the Theatre Royal, which seems to have changed its name following the closure of the Westminster Repertory Company, and was known as the Theatre Royal from Carfax Theatre.

In 1981 Horsham District Council made a very public pledge to keep live theatre in Horsham. The obvious venue was the old Capitol Theatre, but the building was in the way of major redevelopment of Swan Yard. Horsham Urban District Council had originally bought the site in 1953 for £27,000 and now M&S were offering £1.5m for it. The Council agreed to spend £200,000 to demolish the old theatre, and at same time purchased the old ABC Cinema in North Street. The building cost £200,000 and a further £900,000 was set aside to convert it into a new theatre. This theatre became The Capitol, opening in 1984, and the rest is its history.

Published: 17 Jun 2020