Jeremy Knight discusses the history of book-selling in Horsham.

On the 3rd of September, some 600 new books will be published in the UK, a record amount. This is due in part to the effects of COVID, as publishers have held new releases back in order to catch the Christmas push. In fact, so many new books are being published that even the biggest bookstores in London do not think they will have space for all the titles. This remarkable landmark for a medium that thought to be dying 15 years ago (but is in fact in rude health) has led to us investigating book-selling in Horsham’s past.

Recent research has shown that many of the ideas about literacy in the past are wrong. It is often assumed that people in the past could not read yet, after printing was invented in the 15th century, some 20 million books were printed in Europe. Despite this explosion in print the connection between reading and “righting” is relatively new. Many people could read, but not write. Additionally, not all reading material was printed so the idea that manuscript publication ceased after the invention of printing press is now known not to be false. In fact, for publications that had a small distribution, hand written copies were the best option.

Shipley Church had a bestiary (book of beasts) as early as the 1300s and although we know of other books circulating around the Horsham area in the Middles Ages, our story of book-selling did not really start until the 17th century. The town was however, home to a number of people with personal libraries - a subject for a future article - but for now, we are looking specifically at booksellers. Horsham had no bookshop in the town for many years, as shown by the fact that there is no mention of a stationer or bookseller in the parish registers from 1541 to 1635, in the inventories from 1611 to 1774, or in the deeds and apprentice registers from 1572 to 1798. There are however several references made to a chapman. Chapmen sold chapbooks, 24 page booklets sold for 2d or 48 page sold for 3d that were crudely printed on soft paper so that they after being read could be used for another less noble purpose. In addition to this essential resource they also sold other trifles. According to probate lists Horsham was home to merchants who sold books as well as other items. For example, buried in the 1679 inventory list for the mercer Michael Woodgate, amongst the “goods in the shopp” is a copious list of textiles, gunpowder, spices and dried fruit, needles, yarn, waistcoats and other useful items:

(Image of medieval bestiary, copyright British Library)

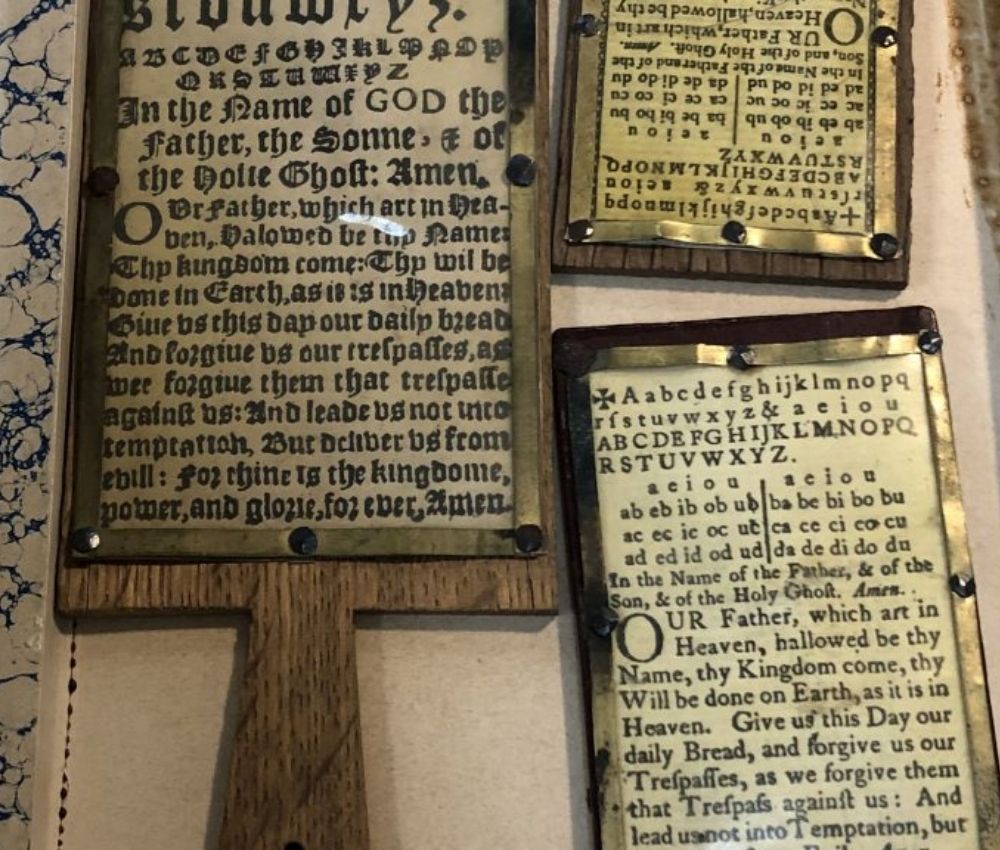

“It a pccll of Hornibookes? Primmers combes thred & thredbuttons Tobacco boxes logrings? Hookes & eyes & whipcords washbrills? & pads “ valued at £1 4s 6d… It. 2 bibles 5 testaments 3 Crammers & 2 other… bookes & a customery booke” valued at 15s 6d.”

A “hornibooke” or hornbook is a small wooden paddle-shaped, hand-held board usually with the alphabet and/or catechisms attached to one or more sides. Hornbooks were generally used as primers for study. It would have been covered with a thin translucent sheet of horn, hence its name. The “customery booke” (customary book) is interesting as it probably a book of manners or customs rather than a law book relating to manorial duties. When King Charles returned to England he brought with him new modes of address and customs at court. People, who wanted to know how to behave and make the right impression had to learn these new modes of behaviour, for example no spitting in the fire, in order to mix with the right society. Despite selling some similar products, Woodgate’s shop was not a true bookshop, but was instead a shop that sold books amongst other items, many of which had no apparent connection with the book trade.

(Image of hornbooks, copyright Duke University Libraries)

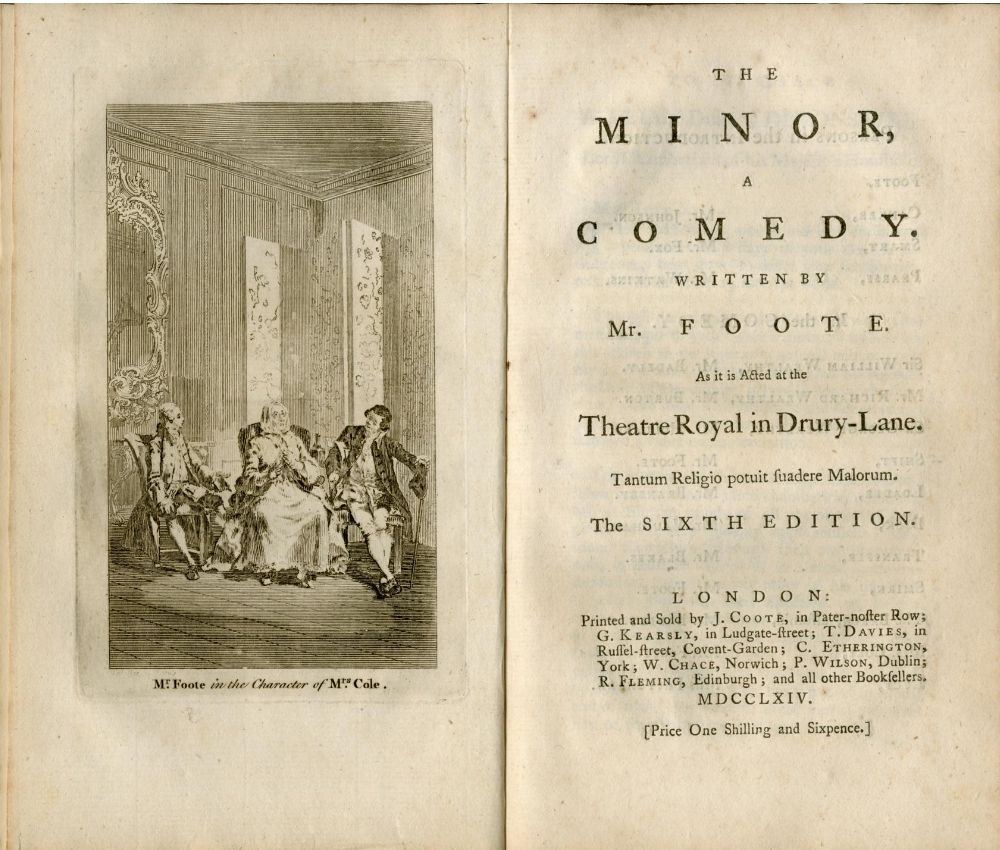

In the 18th century Horsham saw the birth of two people who would gain such fame for publishing books, and selling them in their premises, that they would gain a place in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Bernard Lintott and his decedents who used the sign of the Cross Keys, and John Coote. However, neither opened a shop in Horsham. Although Arthur Lee, from Lewes, supposedly printed the first book in Horsham in 1768, a story of a journey to Aleppo, there was no dedicated bookshop to sell it from.

In 1782, the solicitor and writer Anthony Highmore travelled from London to Brighton and wrote an interesting travelogue in the style of Sterne’s then highly popular and recently published “A Sentimental Journey in France and Italy”. Highmore’s account was never published and lay unread until Charles Hindley found it and published it as, “A Ramble on the Coast of Sussex”. Part of the text deals with a visit to a Horsham bookshop where the author took part in a discussion about the literature of the day before discussing the nature of romance and marriage. It is a fascinating account because of what it reveals about society in Horsham:

“Having returned our chaise, I looked in at the Bookseller’s – not more to see the books, than the smart female figure, which traversed the floor in very quick paces. She was dressed in a white gown tied with pink ribbons – could not boast much height, and what she wanted in beauty she made up with taste, fashion and manner…I found by her mode of speech she was not unused to lively conversation…”

The comment about her conversation suggests that he had expected a level of ignorance in her speech, perhaps not expecting a high level of “politeness”. However, as becomes apparent, the female shopkeeper’s air of learning was not arrived at by reading, but through listening to and aping her betters. She later discusses the culture of ignorance in Horsham, even amongst her clientele. Perhaps she felt that she could not talk to her well-read local customers due to a class distinction that has not been borne out by other writers in Horsham at this time. She may speak well, possibly without the coarseness of the Sussex dialect, but whilst innately intelligent she was not an avid reader:

“You have some well chosen books here, Madam” “Yes, Sir, but I never read- I perceive you are a reader, and I have long wished to meet with a person of judgement, who could put me into a course of reading, instructive and entertaining” “I should have supposed, Madam, from your choice of Language, that you already seen the best Authors in the lines you mention”. “No, I never met with a Man of Taste yet, Sir, - and as to the Women, you know” ….I recommended to her the “Sentimental Journey” – she readily took it down from the shelf. Later “we were interrupted by the entrance of an officer, who came to return the first volume of “Cecilia”

This suggests that it was a well-stocked bookshop with bound volumes, as well as a subscription service where people could rent the books, rather than own them. The shop assistant could read but didn’t read the shop stock, so Horsham shoppers would not get the staff recommendations that you see in book stores today. She didn’t have anyone to talk to about how she could improve her education and get recommendations for the best authors, and fashionable books of the time. Highmore approves of the stock in the shop but it is apparent that the lady did not select them herself as she had no knowledge of the authors. Perhaps a relative or business associate did the selection, but if so from based on what information? It is possible that the shop staff accepted customer requests, followed reviews in the London press, or had reciprocal arrangements with London agents. Unfortunately, we have no idea where that specific bookshop was so it is difficult to find out more.

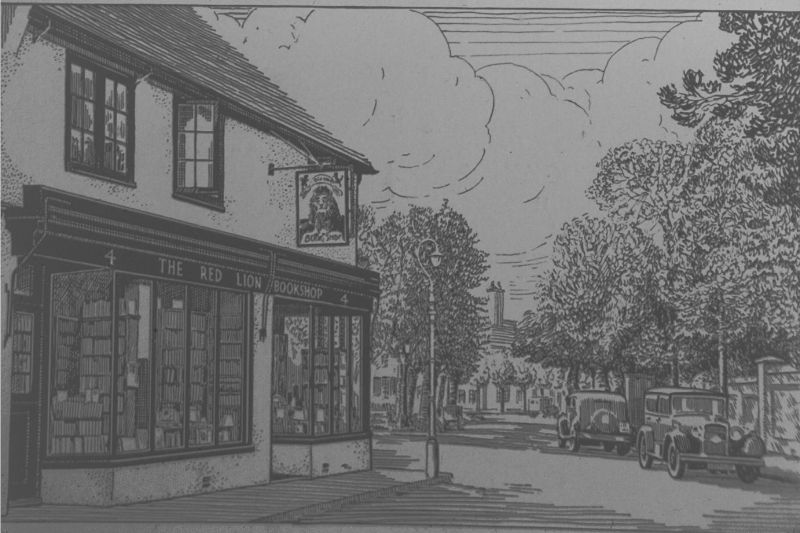

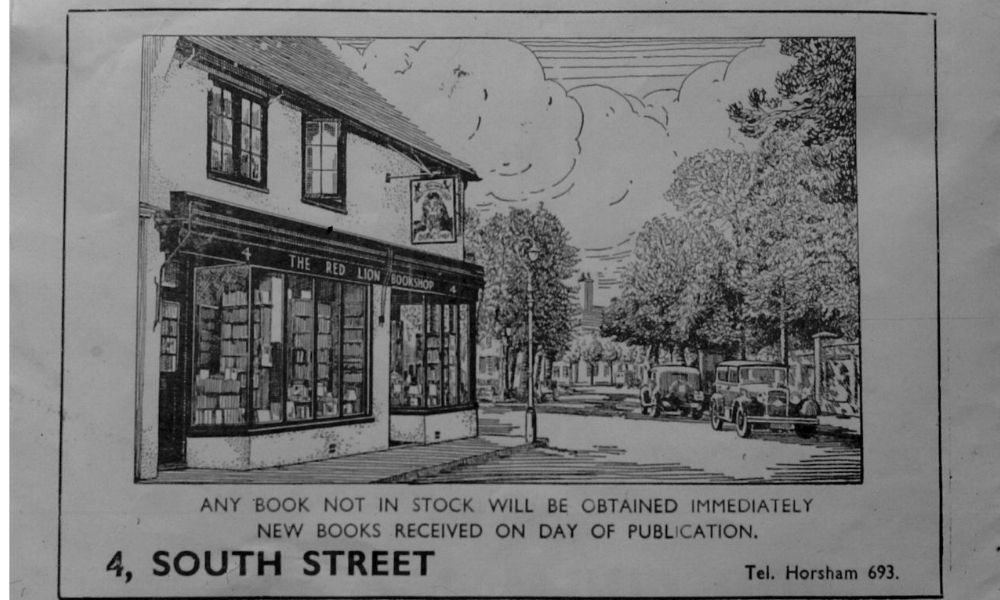

Throughout the following century there is no mention of a bookshop in Horsham. A stationer or two who probably sold books as well, but not a dedicated bookshop. Later companies like Boots the Chemists started selling books or operating a circulating library. The museum does have a grand sign for the town’s bookshop – The Red Lion hanging in the barn, but until its opening Horsham didn’t have a dedicated bookshop.

Published: 28 Aug 2020