The first in a two-part series looking at farming practices in Horsham's past.

Exploring our history

As Horsham celebrates local produce with the Virtual Big Nibble: Future Food Festival, a festival that originated out of the horrors of foot and mouth disease back in 2003, it is an opportune time to look at a fundamental but almost forgotten part of Horsham’s history - farming and agriculture.

Less than 80 years ago, within the boundary of the old Urban District council there was still farmland and a regular livestock auction. Yet today there is very little evidence of farming in the town apart from a produce market. Therefore, in the space of two generations a 3,000-year-old tradition has virtually disappeared.

The first hard evidence of farming in Horsham District was found at Chesworth. An Iron Age loom weight was found, along with other similar material, suggesting a farmstead. Its location by the side of the river was probably chosen to exploit a woodland pasture amongst the surrounding trees. We know that one of the key things about farming and agriculture during the Roman period (43 - 410AD) was that, owing to high levels of taxation to pay for turning mud bricks into marble and to fund the military, land was heavily exploited for cash crops. You had to be an efficient farmer.

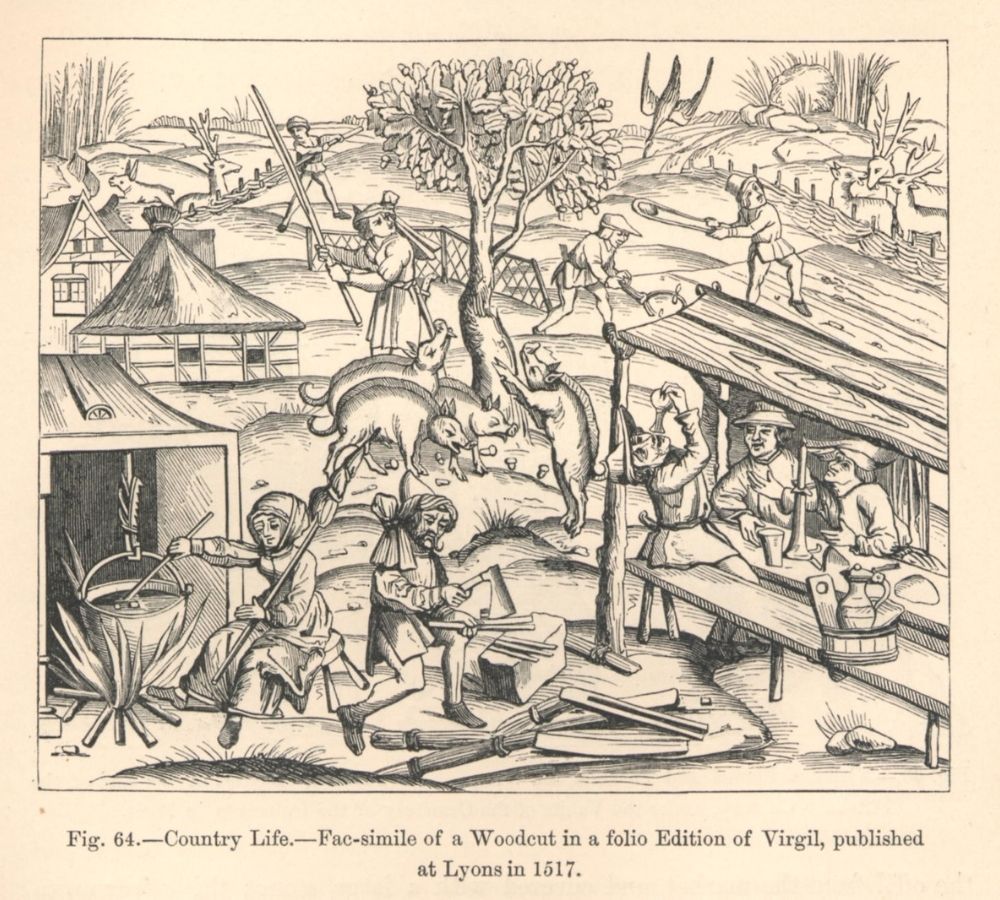

After the Romans officially left Britain in 410AD, the Saxons invaded and settled. The country was sparsely settled at the time due to a plague that wiped out large numbers of people. The Saxons did not practise intensive cultivation to produce cash crops, nor were they “townies”. They settled on large estates, rather than in towns, and followed a more natural style of farming: following livestock to seasonal pastures in the summer and returning to the home farms for the winter months. The people from the Saxon settlements along the coast of Sussex started to move into the higher lands of the wooded north, creating seasonal pastures and farms there.

In the 8th century, the Saxon settlement of Steyning, with its port and important Saxon church, was probably the dominant economic centre. Nearby there was a large Saxon estate based around Washington. All around present-day Horsham are place names that have Saxon origins such as Roughey (later spelt Roffey), where “rough” means deer and “hey” means fence. Chesworth was “Ceoldred’s farm”, and this clearly shows that Saxons were working the land there by the 9th century if not long before. This practice was confirmed in land charters, including the first one that mentioned a place where horses breed, Horsham. The settlement arose in 947 when the people of Washington, 15 miles to the south, were given additional land for pasture.

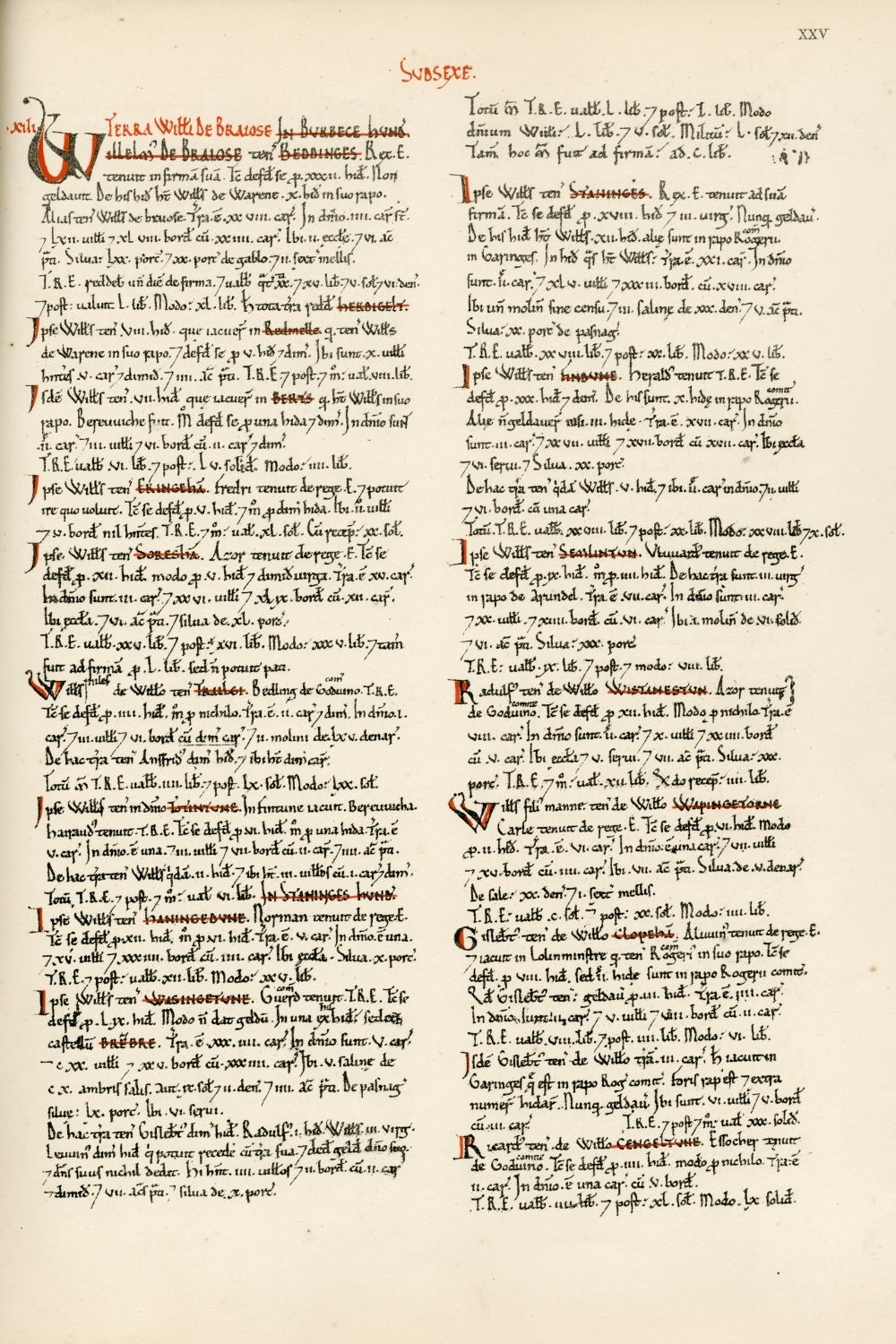

One of the great documents in British history is the Doomsday Book. It was written by Anglo Saxon civil servants for William the Conqueror who had invaded in 1066 and wanted to know who owned what, and how much. It provides a highly edited snap shot of England in 1086. Horsham is not directly recorded, which suggests it was not worth anything. However it is mentioned, but not under Horsham, under Washington. The record has a reference to the swine pastures that was ‘70 pigs’ worth of woodland pasturage. This indicates that Horsham was by now a woodland settlement capable of supporting about 500 animals. The Normans also changed the general development of the area around Horsham by creating a forest, an area for hunting game. What is also clear through the surviving documents is that the woodland was “farmed” through forestry in order to provide wood for the armament industry, and charcoal for the iron industry.

The 14th century

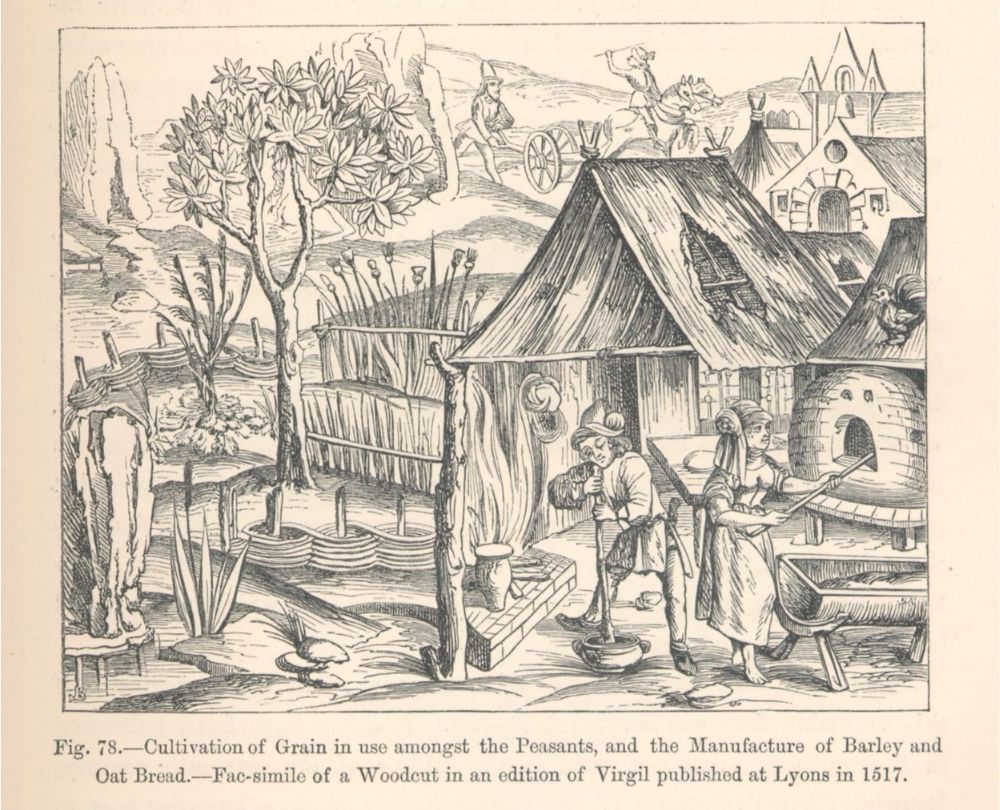

Farming and agriculture continued to be a key part of the local economy, trade and markets in Horsham relied on it. Foodstuffs were produced here, but also transported up from the coast, walked on the hoof from Wales (Welsh cattle being highly regarded for centuries), and traded at the markets and fairs. Horsham was growing in importance. The 14th century saw a rising population so farmers were moving into the marginal lands, probably including the poorer soils of the Weald. Woodland ‘assarts’ were increasing (an assart is where trees are cut down in woodland and the land turned to arable) as the demand for foodstuffs increased to feed the population. Crockhurst and Marlpost, both in the south of the Parish had assarts in the 13th century; the belts of woodland that we see enclosing land today could be the remnants of these. Following the devastation of the Black Death population growth ceased. Horsham eventually recovered and the Archbishop of Canterbury gave permission for a new Monday market in the Bishopric, as well as two 3-day fairs.

The first market at the Bishopric

Talking of the Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1460 he was granted a corn market at the west of Horsham on land that today is known as the Bishopric. It was one of many markets in the town. Corn was a staple foodstuff had to be milled, and at least one mill is recorded in Horsham. In 1231 when the rector’s Corn mill was given to Rusper Nunnery however, it is apparent from the records that corn was not grown here in any great acreage, suggesting that the mills were set up to mill corn from outside the area. This is not that surprising if you consider the heath land and poor soils in Broadbridge Heath, North Heath, and Mannings Heath. They didn’t get the name “heath” for nothing. That is not to forget Horsham Heath was also later called Horsham Common.

The story doesn’t end here, but that’s all we have space for this week. We hope you found it interesting. Keep your eye out for next weeks’ continuing exploration of the history of Horsham’s farming industry.

Published: 18 Sep 2020