The second part of Jeremy Knight's look into farming and agricultural practices in Horsham District's past. This week he covers the 18th century and beyond.

Today we are continuing the fascinating history of Horsham’s farming industry that began last week. Having looked at early settlement of the region, through to the Middles Ages we now move on to the 18th and 19th centuries. The theme was chosen to coincide with the Virtual Big Nibble: Future Food Festival, a wonderful celebration of local food and drink businesses across the District – in a virtual format.

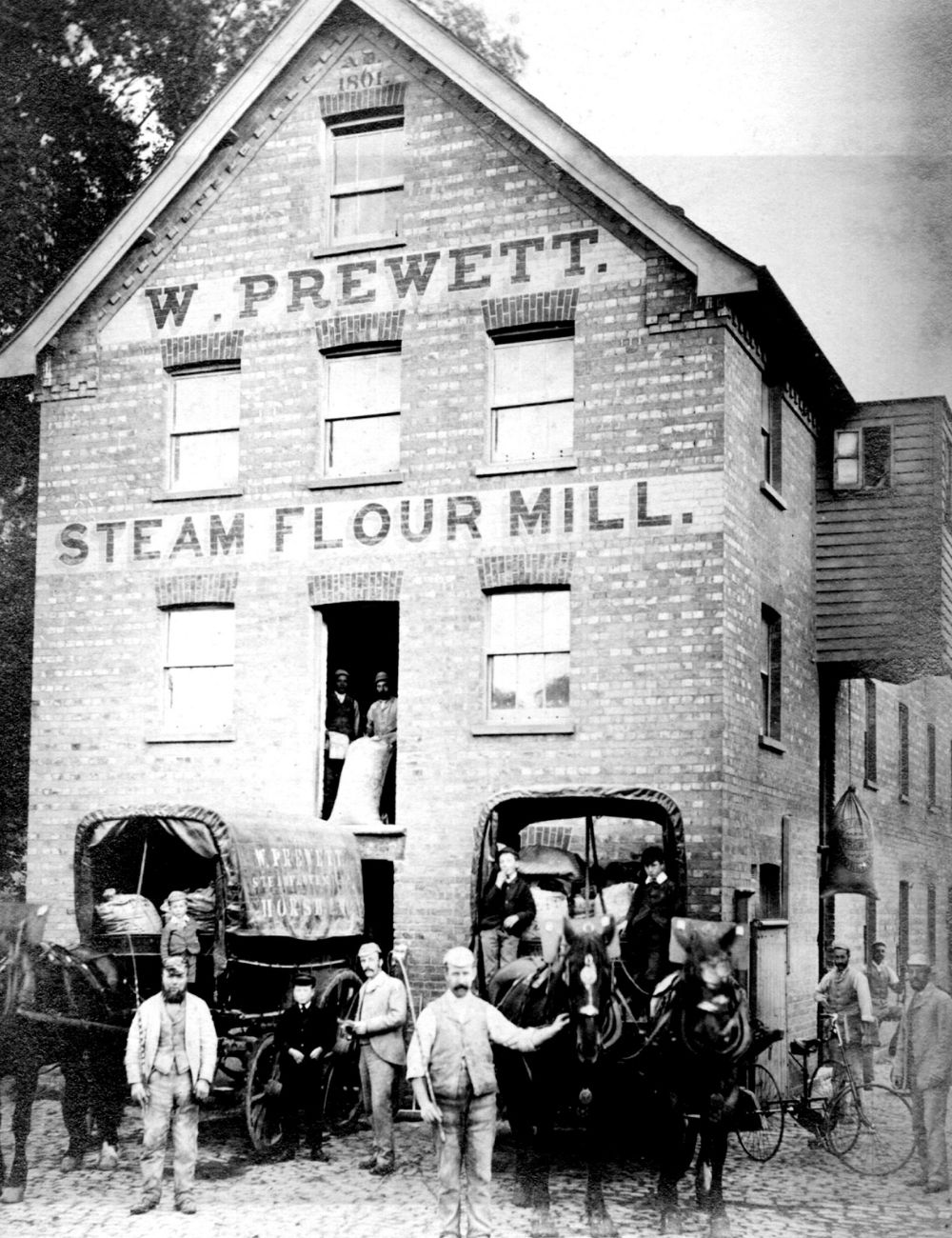

Daniel Defoe mentioned in 1724 that corn was “cheap at the barn, because it cannot be carry’d out, and dear at the market because it cannot be brought in”. This was due, in large part, to the poor quality of the roads. Cattle did not demand roadways, but corn did, therefore waggoners needed good roads to get the corn from the market to the population at large.

After the devastation of the Black Death, it was not until the 18th century that there was another transformation in farming practices. One of the great movements recorded in the 18th century was what became known as the agricultural revolution. Whether it was a “revolution” or an evolution is for others to debate, but what it did see was renewed interest in the land. The Tories, who were in effect disbarred from the politics of government thanks to the arrival of the Hanoverian Georges, left London and spent their time and energy on improving their land - both agricultural land and creating gardens around their homes. If they could not manage the state, they would manage nature. The fantastic Georgian houses were built on wealth from farming at home and colonial farming with slaves abroad.

John Wicker was a successful brewer and merchant, who lived at what is now known as Park House. In 1703, he appealed to Queen Anne to open a new cattle market in Horsham, his argument being that it was good for the town and more importantly for London, which was growing. The market was approved in 1705 however, by 1723 the Borough market had ceased, as there simply was not enough trade, either locally or with London, to sustain the new monthly cattle market.

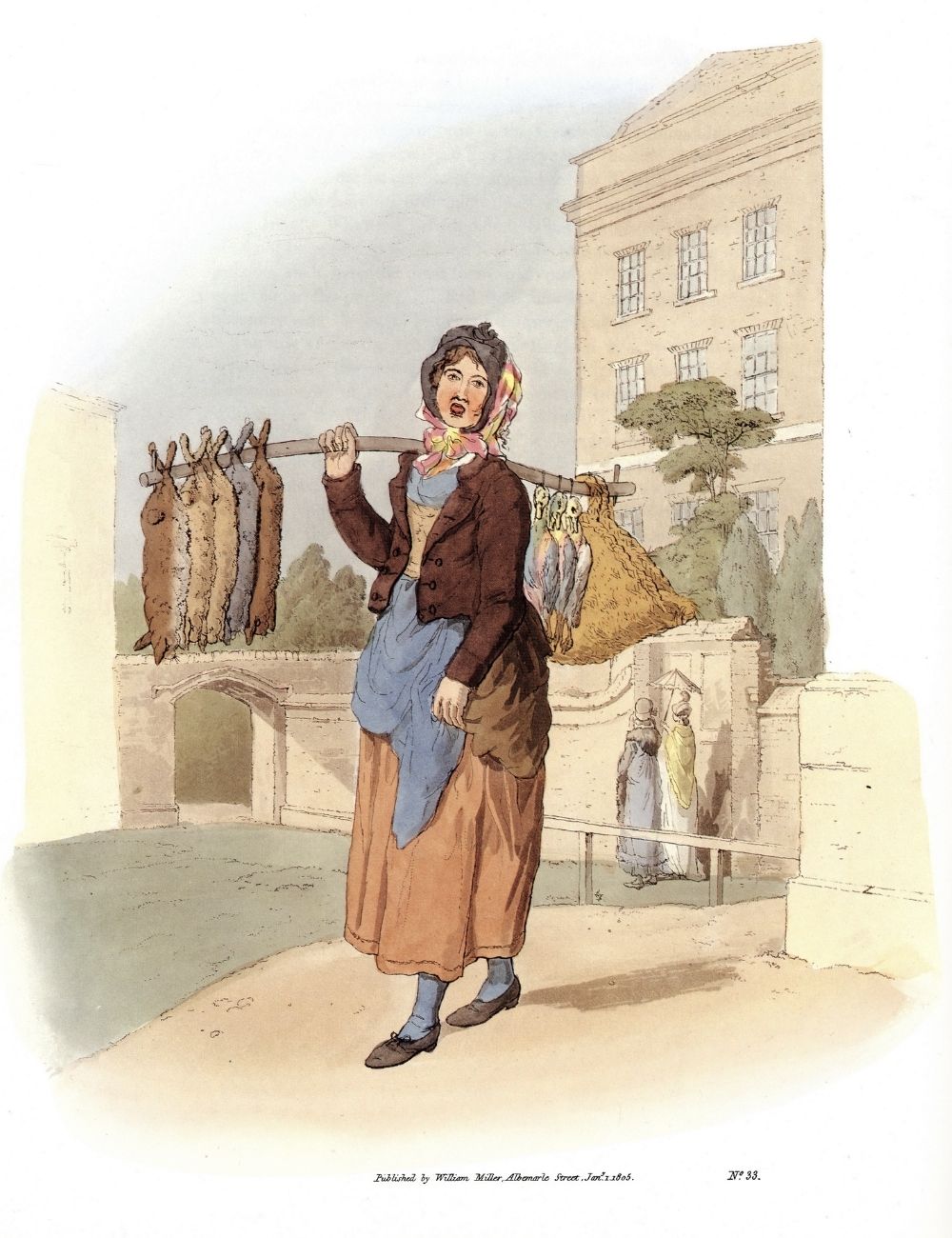

It is easy to forget that Horsham was still very rural at this time. As late as 1844 there were 70 farms in the parish. The degree to which the farmer improved his or her land was dependent on the individual; there was no state interference either through subsidies or through regulation. For example, in the 1720s one Horsham farmer had 70 ewes, whilst in the 1740s they grew more oats than wheat. Potatoes were grown on the Denne estate in the late 18th century as horse fodder and barley was grown, perhaps for the brewing industry. Peas were mentioned in the 1740s, not for human consumption but for animal fodder, and in the 1780s at Chesworth Farm, turnips and clover seeds were also grown as fodder. In 1750 there was one haymaker mentioned in the parish. In 1717, records indicate that fruit was being grown in the parish. This diverse record suggests that farming was predominantly pastoral rather than agricultural: growing livestock, including poultry that Daniel Defoe recorded at Dorking market, which would have suited the poor soil prevalent throughout the parish.

The enclosure of the common

A large number of books and articles were published in the 18th century suggesting how farmers and landowners could improve the profitability of their land through crop rotation, new breeding techniques, and fertilizing the soil. However, it is difficult to know who in Horsham read such books and incorporated those methods into their practice, except to say that clover and peas are very good crops for putting nitrogen back in to the soil and were promoted for that, along with the promotion of turnips as an animal feedstuff.

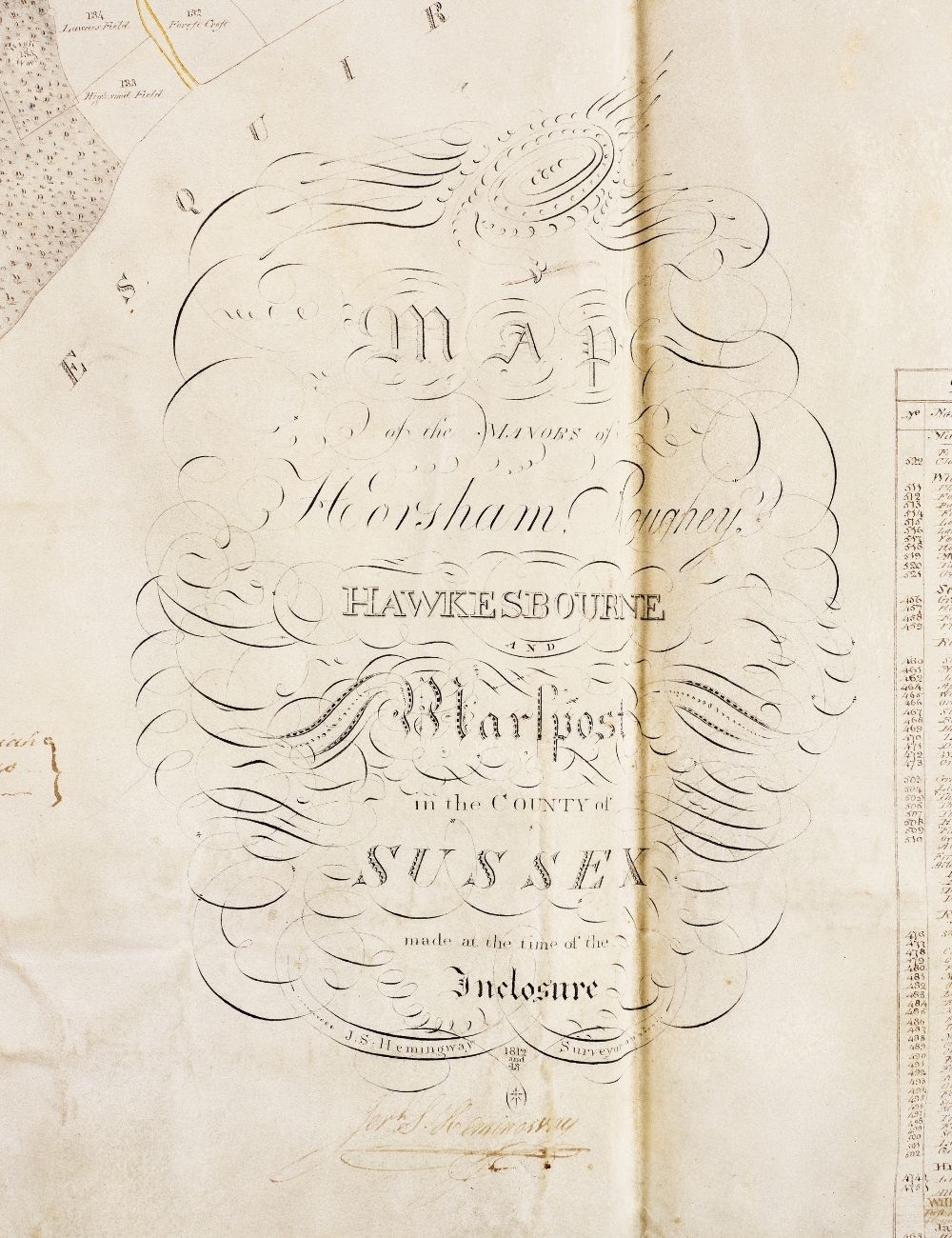

However, the key part of the agricultural revolution was enclosure of the common, which in Horsham did not occur until 1813. Horsham Common stretched for around 750 acres in an arc covering the north and east of the parish. The Common was owned by individuals, but ordinary people had the right to exploit the land for things such as collecting firewood and grazing their animals, however they did not own it. In Horsham, the burgesses (those that owned burgage plots), had pasture rights to the Common, as did the tenants of Roffey, Hawksbourne, Marlpost and Shortsfield manors reflecting its medieval origins

A snapshot of livestock in 1803

The reason landowners did not improve the common land was that, if cattle and other livestock had pannage rights they then had the right to eat the plants growing on the Common. The Common could only be turned over to proper effective and economic farming use either if the commoners acted as a corporate body for the benefit of everybody, or if commoners’ rights were made null and void. Therefore, whilst the agricultural revolution was occurring, large areas of Horsham’s farmland saw little or no improvement, unless it was in selective breeding of livestock, something that the records do not tell us.

Thanks to the Napoleonic wars and the demand by the state to know what was available, below we have a good snap shot of the livestock in Horsham Parish in 1803.

Schedule 1: Livestock | |

|---|---|

Fatting oxen | 46 |

Cows | 325 |

Steers, heifers and calves | 486 |

Colts | 34 |

Sheep | 1237 |

Lambs | 266 |

Hogs (for bacon) | 363 |

Sows (for sausages) | 138 |

Pigs (for best pork) | 695 |

Riding Horses | 137 |

If the appearance of sheep seems strange, the museum has a fine silver inkwell given to the then owner of park House as a prize for breeding sheep. A great deal of Horsham farmland was probably used for livestock, as shown above. Sussex was different from most counties in having both a Sussex Cow and a Sussex Sheep that were described as:

“the most distinguishing feature in the husbandry of this county…The thorough-bred Sussex Cow has a deep red colour, fine hair, and the skin mellow, thin, and soft; a small head; a fine horn, thin clear and transparent, which should run out horizontally, and afterwards turn up at the tips. The Sussex cows are not to be compared with some other breeds; but what they want in that point, they make up in quality. A good cow will give five pounds of butter a week in the height of the season…”

The South Downs Sheep, a breed that was genetically engineered through selective breeding in the 1780s, had gainied popularity across Sussex by 1813. Horsham has been noted in a number of accounts for its poultry sales, but rabbits have not been mentioned, except with regard to the dragon of St Leonard’s Forest in 1614. However with the construction of large rabbit warrens in St Leonard’s the rabbit was an important cash livestock:

“Rabbits, which flourish in proportion to the size of the wastes, are, therefore, productive in this county. From Horsham and Ashdown Forests considerable quantities are sent to the markets of the metropolis….”

The impact of 19th-century population change

Britain’s population was increasing and between 1811 and 1841, Horsham saw its population rise from 3839 to 5765, a 50% rise that mirrored the nation as a whole. However, the number of people farming had seen a decline in Horsham dropping from 349 families out of 719 in 1811, to 308 families out of 1008 in 1831. Although there had been an apparent drop in families cultivating the land, in real numbers it was not that great a decrease. It reflected the still ongoing land ownership pattern identified above. In 1844 a detailed map and report was written, the Tithe Map, and it offered an excellent overview of the parish.

In all there were 70 farms over 50 acres in area. Within Horsham, there were three areas of allotments leased out to the Labourers Friend Society. By 1844, half of the parish was put over to arable, with one quarter as meadow or pasture. In 1841 the Arundel and Bramber Agricultural Association held ploughing and stubble cutting competitions at Chesworth Farm. It should also be noted that about one ninth of the parish was woodland ideal cover for game, and hunting continued to be a popular pastime. It may also have provided the raw materials for broom makers who were recorded in the parish in 1784, 1812/13 and in 1862 when six out of the 23 brush and broom makers in the county lived in the parish.

The open nature of Horsham town itself can be seen in the development of nurseries in the town. Allman’s nursery, on the corner of Park Street and East Street, was founded in 1828. The nursery stretched to 10 acres by 1866, and went as far as what is today Bartellot Road. It grew forest trees, ornamental trees and exotics. In 1844, there were two other nurseries on the corner of Brighton road and St Leonard’s Road. Who were the buyers of their plants? Horsham did not have a railway yet so it is unlikely that Allman’s serviced the London market at its inception. By 1841 with the trains only available at Three Bridges, the nurseries might have grown plants for the growing London market, delivering to the station by wagons. What was good for London would have been copied by some of the more wealthy families in the Horsham area.

A shift to milk and the tidying of the town

By 1861, much of Horsham’s common land had become arable, but now there was a shift with the growing demand for milk from London. Therefore, between 1875 and 1909, the number of cattle increased in the parish by half, and the amount of permanent grassland increased from 2,632a to 5,230a. It might have been expected that the agricultural depression would have seen a collapse of the local corn and livestock markets. However, they survived and flourished, probably because of Horsham's closeness to London and its transport routes. Horsham's corn market was seen as one of the chief Sussex markets in 1883, and the poultry market had moved to the Swan Inn away from the Carfax in 1882. Later it would move to the Black Horse Inn. This move in itself is an important indicator of the decline in agriculture in Horsham's economy.

Horsham corporately wanted to see the Carfax, the centre of the town, lose its agricultural roots and become a public space rather than a marketplace. The town sought a tidying up and removal of the "muddy boots” of the farmer. Such moves would continue for the next decade until, by 1892, with the erection of the bandstand the transformation of the Carfax was complete. That is in the future; by 1887, the Monday poultry and Wednesday corn markets were still active though cattle were sold on the alternate Wednesday, suggesting that the impact was being felt. The popularity of poultry was due again to Horsham’s closeness to the growing urban centres.

The agricultural depression was also important to Horsham’s story for a number of reasons, not all related to agriculture. The main one being the rise of the new landed elite, men who made their money in the city and bought up farms or uncultivated land turning them in to a hunting estate. This in turn would feed into the creation of a culture and an image of a place that Horsham still has today - though it is declining with the impact of the 1980s, that of the county/country town. However, back in the 1880s and 1890s Horsham’s landscape was in many ways reverting to the way it had been in medieval times with hunting parks (now called shooting estates). Whatever the reason the effect on Horsham was palpable, Horsham became a desirable place to live. Within Horsham, the changes can be seen in the agricultural statistics:

| 1875 | 1933 | |

|---|---|---|

Wheat | 1,493a | 300a |

Oats | 1,040a | 262a |

In 1875, the Parish had 663 pigs and 1,781 sheep. By 1909, the number of sheep had fallen to 1,129. This large number of sheep was probably the reason for the 5th April Fair, mentioned by Dorothea Hurst in the second edition of her history, for she comments that this fair had no legal entity but had sprung up for selling sheep. The main sheep fair was, of course, the one held at Findon each late summer/autumn. By 1933, there was said to be a decline in beef production in the parish, though there were 1,418 dairy cattle and pig numbers were still high. Milk production was high. One reason that the amount of produce did not decline to the extent of land under cultivation was that more and more mechanisation was taking place.

The town liked to retain its farming roots in the 20th century, with agricultural and livestock shows. The museum society actively collected farming equipment in the 1960s to reflect this interest, but due to the growing demand for housing the number of actual farms declined dramatically in the 1920s to 1960s.

Published: 22 Sep 2020