We look at that key feature of a home, the hearth, which has historically been central to homemaking.

With the sudden onset of the cold snap, we are all appreciating the warmth of central heating. This is probably the greatest change in the development of homes, as it means people can now live in dispersed rooms, rather than huddled in together. Imagine social distancing if there was only one source of heat for your whole household. Nowadays, unless people have a wood burning stove or coal fire, they quickly forget the importance of the hearth. How many people remove old chimney breasts to make rooms larger? How many new homes have chimneys, and are they ornamental rather than functional? This week we look at that key feature of a home, the hearth, which has historically been central to homemaking.

The archaeological record is full of evidence for the hearth, from patches of burnt soil to carbonised wood fragments, or a ring of fire-cracked stones in the centre of a floor that suggests an opening above the fire to let the smoke out. At Horsham Museum some of the roof timbers show evidence of burning caused by an open fire, not by an accident. Some fires had hoods, just as today's kitchens often have a cooker hood to catch steam and smells, then its purpose was to capture the smoke.

As well as a central fire, the occupants of hall houses and hovels used animal proximity to keep warm. It was the creation of separate spaces, the separation of them and us, that led to significant changes in the home. As individual wealth increased along with status, spaces became rooms, and rooms required heating.

Though the earliest known domestic chimney in Britain dates to the 12th century, they didn’t really become part of the average home for another 300 years or more. The smoke was captured in a chimney creating a draught, which in turn improved the efficiency of the fire. However, the enclosure of a flame and increasing its effectiveness led to obvious problems. Chimneys were made of timber, wattle and daub. The hearth also separated from the fire used for cooking food. Cooking fires were often located in the new service wing of houses incorporating the kitchen. At Horsham Museum’s Causeway House the medieval kitchen was built on the side of the house so that it could be pulled away with grappling irons if it caught fire.

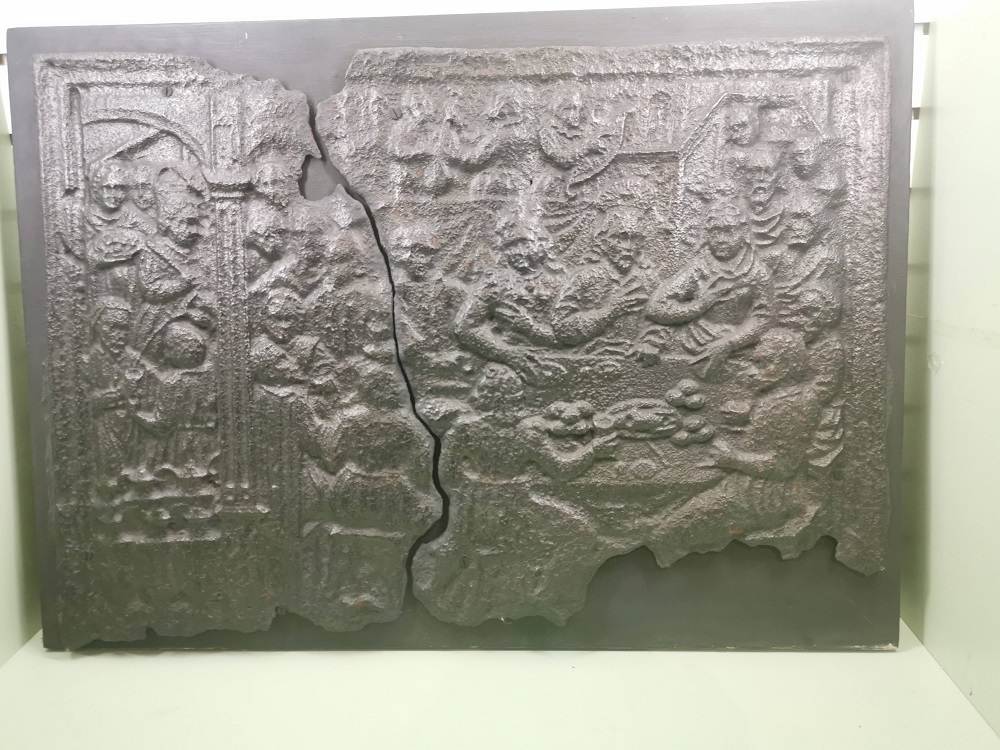

Firebacks

With the increase of fireplaces in the home, the fireback, that large lump of cast iron made in the Weald that adorned the backs of the chimney to stop burning of the wood and to reflect heat, rose to prominence. Although bricks were made at this time, they were not popular in the home. Their popularity grew following the Great Fire of London, but even when brick chimneys were built in expensive homes, firebacks remained. Such is their iconic status, they have become a much sought-after antique. Despite this, firebacks have only recently attracted academic research. Thanks to the work of a former head teacher from Crawley there is a web site that explores fireback’s in all their glory based on his seminal book. Jeremy Hodgkinson’s section of the site includes a searchable database, history and interesting photographs of a number of firebacks including those held by Horsham Museum. With the introduction of multiple fireplaces and hearths, chimneys were built in the middle of the house or on an end wall, with the number of chimney pots indicating the number of hearths. The chimney stack, the bit that rises above the roof, grew in height as it stopped embers falling onto thatched or wooden roofing. They also became a status symbol, developing ornate brickwork. In Horsham, with its stone roofs, such chimneys purely portrayed the wealth of the householder. The pot on top was cheaper than building the brick stack, but it too became ornamental as well as functional. Curb appeal and projecting status is nothing new.

Another feature of the hearth, fire dogs (or to give them their proper name, andirons) are also popular antiques. However, because they are portable and not built into the house, they are harder to date. Though they existed in medieval times and earlier, the more well-known cast iron versions appeared in England around 1540. Though they could be plain and simple, the fronts soon became decorative with other metal embellishments. Firedogs came in pairs to support logs and allow air to flow underneath causing the flame to burn more efficiently. By the middle of the 19th century they became less popular as the stove developed, but by then they had become a collectable antique.

Today we pay a community rates based on a property value, but in the past the importance of a hearth was such that the government introduced a tax on it. King Charles II expected to have an income on his restitution to the Crown in 1660. Parliament agreed to £1.2m a year. Unfortunately they were £300,000 short, so came up with the idea of a Hearth Tax. The 1662 Act introducing the tax stated that 'every dwelling and other House and Edifice …shall be chargeable ….for every firehearth and stove….the sum of twoe shillings by the yeare'. The money was to be paid in two equal instalments at Michaelmas (29 September) and Lady Day (25 March) by the occupier or, if the house was empty, by the owner. The tax lasted until 1689 and until the census in 1801 was the most detailed account of the properties in Britain. The government could inspect properties to ensure tax was correctly paid on the number of hearths. The importance of these tax lists is such that Roehampton have a dedicated website to its study, though unfortunately Sussex records have not been added to the site yet, but it does set out why such records are so important.

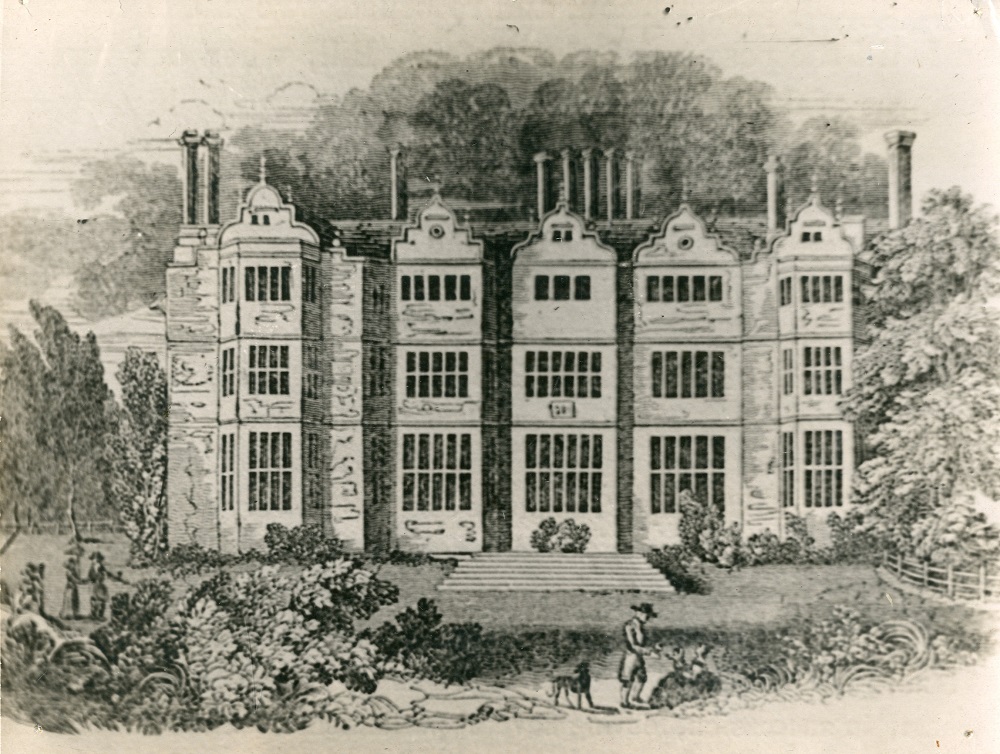

However researchers, such as the late Dr Hughes, have transcribed such records for their research. Through that research we know that Horsham’s Hills Place, a Jacobean stately home pulled down in the 19th century, had 22 hearths in 1670 according to the hearth tax, the largest number in the Horsham area. This indicates the property’s size and status. The tax itself was withdrawn by William and Mary to improve their popularity, nothing new there then.

Hills Place Horsham

Thanks to the popularity of Mary Poppins and popular folk stories, the chimney sweep is a well-known character in literature and song but the reality of their lives is no singing matter. Early chimneys were wide open and required little cleaning, however as sea coal was increasingly used instead of wood creosote would build up on the inside. Also, to improve the fire chimney flues became narrower, measuring around 9 by 14 inches. The more fires in the home the more flues were required and they often had angles in them to direct the smoke and gasses to the chimney. Boys, and occasionally girls, aged as young as 4 and often working in the nude, would be sent up the chimney to scrape away the creosote and dust, or if the chimney was on fire to extinguish the flames. Children could easily become trapped so occasionally flues would need to be broken to get them out, other boys might be sent up to help them out, or, sometimes they may be left to die. The skin of the boys would be hardened with salt rubbed in. Such were the conditions they worked in that in 1788 an act was passed to improve the situation. Numerous other acts followed, but it wasn’t until 1875 that the practice was stopped and chimneys were designed differently allowing sweep brushes to clear them.

Today we have thermostatically controlled heating, radiators, and fan heaters scattered throughout the house heating individual rooms. Despite this the hearth is still central to the home, as shown in the trend for the kitchen to be the centre of the house. Today large kitchens incorporate sitting, dining, hosting, relaxing and even have beds for pets to sleep in as shown in recent adverts. So after 800 years when the large hall house had one room heated by one fire and life continued around it, with animals living with humans to keep warm, we have updated our living quarters but we still have the hearth as the centre of the home.

Published: 08 Jan 2021