A look at corruption in 18th Century Horsham

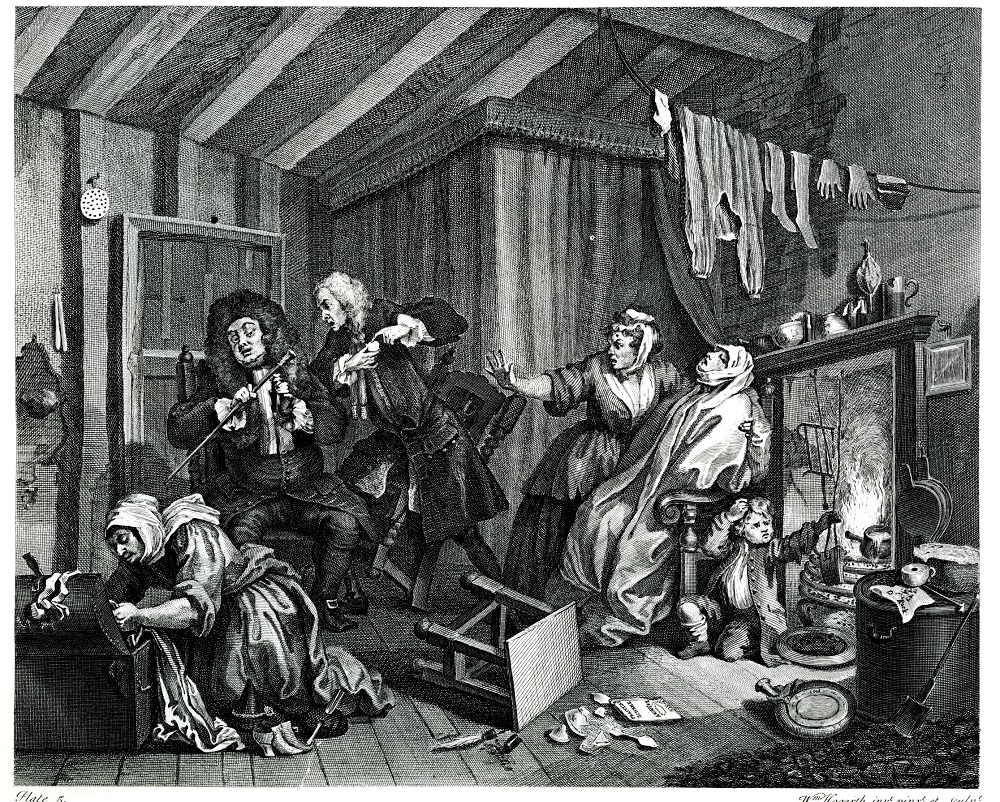

The popularity of Harlots on the BBC has led many people to wonder how true to life the story was. Perhaps not the specifics, but the background of open prostitution on the streets of London and the corruption of the courts in the 18th century. In a culture of extremes (rapidly rising wealth, polite society, easy money and grinding poverty, starvation and cruelty), exploitation was the rotten underbelly of society. William Hogarth, who so vividly captured 18th century life, showed it all in his morality paintings and plates: “A Harlot’s Progress”, “A Rake’s Progress” and “Industry and Idleness”. In fact, images from “A Harlots Progress” are used in the title sequence for the television series. But that was London, what about Horsham? Surely these things did not go on in the ancient market town dominated by the church and County Gaol, with its weekly fairs and meetings of the justices?

The popular 18th century rhyme, “Ridge’s for Riches, green for poor’s, Billingshurst for Prety Girls, Horsham for Whores” suggests that it was the norm, as do some remarkable documents held in the Horsham Museum archives. They give a glimpse at a world on the make, of corruption and exploitation at all levels.

Smuggling was probably the most accepted corruption. It caused the first “war on drugs”, as the military were employed to stop smugglers. Custom officers were initially employed to stop exportation, but by the 18th century it was importation that they tried to stop. Tax was levied on sin, just as it is today, the drug of choice being alcohol (brandy), tea, and fancy goods on which there was a tax.

The trial of Edward Jarvis in 1721

In the summer of 1721 John Wicker and Charles Eversfield were the magistrates. In front of them was Edward Jarvis, a leading member of the Mayfield Gang whose smuggling operation was countywide. Jarvis had been injured in his capture by Rogers, Horsham’s Customs Officer. When being presented to the magistrates for commitment to gaol, the Horsham attorney John Lindfield claimed the smuggler had been illegally captured and that if he died from his injuries, the captors would be guilty of murder. Eversfield and Wicker ordered the customs officers to be put in custody and Edward Jarvis into care of the constable, John Chasemore.

The situation then became even more murky and corrupt. Edward Jarvis escaped custody dressed as a woman and then, 24 hours later, 10 or 11 of the Mayfield gang including 4 Horsham men come into town fully armed, searching out Rogers the customs officer. This may have been more of a ploy to throw off the scent of insider corruption or, probably more likely, to silence a witness for good. The Constable, Chasemore, acted as a go-between for Jarvis the smuggler and Rogers the customs officer. Rogers had his price for silence and that was £17.15s 0d. Chasemore paid Rogers £10 immediately but, because Jarvis escaped using his own wit, he did not need to pay Rogers anything. Rogers wanted the £7 owed to him, and Chasemore, who had already paid out £10, couldn’t get the money owed to him from Jarvis and neither could do anything about it.

Charles & Lady Eversfield

Corruption in the judiciary

This, though, is not the end of the story. Sometime later a sweep of the Sussex countryside by Rogers and his men captured 11 owlers (the name for those who carried the smuggled items across the country). They were brought before Wicker and Eversfield who were holding court at The White Horse Inn as Horsham did not have a Court House. Mr Eversfield questioned the owlers until he noticed Rodgers in the room, then he forcibly evicted Rogers so the questioning could be done in private. Eversfield called Rogers back, and enquired under what authority the arrest was made. Eversfield then let the smugglers go free, saying they had been arrested illegally. Was Eversfield bribed? Almost certainly. Was the arrest illegal? Probably not. Was Eversfield getting his own back at Rogers by releasing the men so Rogers couldn’t claim any reward money, knowing that Rogers was willing to be bribed by Jervis and had received £10 from Chasemore? Difficult to say. What we can say is that it was a sorry state of affairs that did not seem to get any better.

This level of corruption in the judiciary might seem strange to us today but it mirrored the corruption prevalent in the body politic. Both Eversfield and Wicker had used the splitting of burgage plots to gain seats in Parliament; something declared illegal in The Splitting Act of 1696. The attorney who acted for Jarvis was one John Lindfield, who had acted as election agent for the Tories and had been heavily involved in the corrupt election of 1715 when he had arrested voters for the opposition and was himself taken into custody of the Sergeant-at-Arms for “divers illegal and unjustifiable practices” when he was the Returning Officer. Another noteworthy incident was the rejection by the crowd of the punishment meted out on one of their own, by turning their backs on the flogging of a harlot. In Horsham the crowd turned their backs on the sight of a soldier being flogged as they too thought it the wrong punishment.

John Wicker

But, like the television series, corruption amongst the judiciary was not seen to be as exciting as the salacious stories in the 18th century. It would be wrong to impugn the moral standing of actresses of the period though we do know they had a colourful reputation, one that was not enhanced by the sorry tale of William Bunn. Bunn, a young ensign, fell in love with an actress who was at a Horsham theatre. Unbeknownst to him, she had an older lover, and accepted the advances of both men. A duel took place in the Carfax and neither man was injured, though the older lover did suffer a scratch. Bunn fled, only to be picked up hiding on board a ship in Portsmouth. He was brought back to Horsham to stand trial but the actress obviously had words and the charge was dropped from attempted murder to damage to a shirt. Bunn carried on his service in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic wars.

Unwanted babies were a major problem, in Harlots it was the bawd who was kind-hearted, though the Foundling Hospital in London attempted to salve the consciences of the wealthy. For people in Horsham it was the Parish who didn’t want to pay for the upkeep, so did what they could to offload the responsibility. In a remarkable document in Horsham Museum archives we have the trial papers of William Sharp. The court papers in 1804 did not mince their words.

William Sharp was approached by Ann Vaus, “a very loose and profligate character”, at 8 o’clock in the evening of 28 March 1803. Mr Sharp had the honour to be a Javelin man to the Sheriff in the Court House in the Town Hall. The woman invited him to go outside the hall, where “she had taken hold of his belt. He resisted the first attack by the nymph but a second time he gave in having been ridiculed by his companions for refusing the lady’s challenge”. She stated he made her pregnant and that her child was his. Doctors came forward to prove that the child could not be his as the assignation took place recently and the baby had fingernails which form in the later stages of pregnancy. However, the court found against Bunn, because the parish didn’t want to pay for the upkeep of the child.

As for courtesans, the programme showed that they had select clients from the monarchy down. Some 150 years after the programme was set, Horsham resident Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, who wrote and published his first book of love poems to his lover, enjoyed the favours of Catherine “Skittles” Walker a famed courtesan, as did the Kaiser in the years leading up to the First World War, and no one thought it unusual. Harlots has been described as a guilty pleasure by some and although it is not a documentary, it did portray life not only in London, but also aspects of Horsham society.

Published: 10 Dec 2020