We take a look at the colourful lives of two well-known World War One spies with connections to Horsham: John G Millais and Wilfrid Scawen Blunt.

It may come as a surprise to our readers that there are two well-known spies with connections to Horsham. These individuals are not usually remembered due to their spy craft, but because of other aspects of their colourful lives. However they did have interesting parallels to a well-known secret agent. One was noted for his bedroom activities, just like the fictional Bond, who has a rather amorous track record. The other shared the rip roaring adventurous spirit of Bond. Both men were active on the Government’s behalf during World War One, and both, just as all good spies do, went back to their usual everyday activities after their adventures and their espionage exploits were soon forgotten; one deliberately so, the other because it was seen as being of little consequence.

John G Millais: Adventurer, big game hunter, naturalist, rare plant grower, artist and spy. Britain’s man in Norway during WWI

At Compton’s Brow on the outskirts of Horsham, lived one of this country’s leading naturalists, artists and Rhododendron breeders. Despite his renown he hardly appears in any accounts of life on the home front in Horsham. This is for the simple reason that he was acting as a British spy in Norway. Aged 49 when the war started, Millais was married to a wife whose first cousin was an Admiral. Perhaps due to this connection he was given the rank of Lieutenant-Commander in the Royal Naval Secret Service, and the position of British Vice-Consul at Hammerfest in northern Norway.

Millais’ war time exploits feature in his book Wanderings and Memories. He recounts his life there in a “Biggles” style of approach, stiff upper-lipped jocularity and good sport rather than real danger:

Previous to this visit to Norway I had made some study of the German spy system, as it was necessary to do so concerning certain work which I had undertaken…That as the men were invalided soldiers or medically unfit to fight “owing to defective eyesight…it was easy to detect them, because; (1) nearly all wore glasses or pince-nez; (2) nearly all carried a German book under their arm to read at dull moments; (3) all, almost without exception, wore German boots and clothes, which are easily recognized by their cut.

Millais then talks about the German spies in language that mimicked his approach to recording wildlife:

Early in the war Germany had in neutral countries probably ten spies to our one, but though so numerous….they were not a particularly intelligent body of men. They nearly always hunted in couples, and, apart from the points of recognition I have already enumerated, had a way of standing about aimlessly or whispering in corners much after the manner of spies in the cinematograph

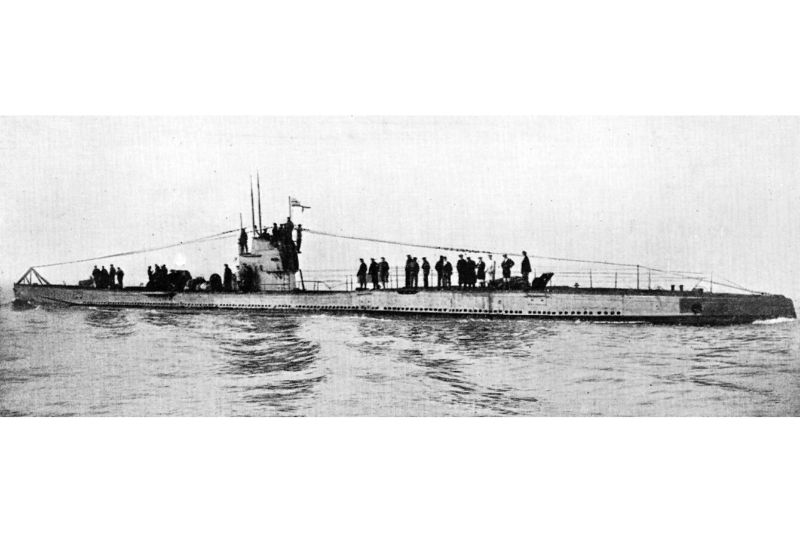

These German spies notified their commanders (by means of carefully hidden wireless telegraphy) of the comings and goings of all Norwegian and foreign ships, and were responsible for the sinking of a great number of the Norwegian ships. Though the Norwegian Government was well aware of these activities, they did absolutely nothing to prevent this leakage of news until 1917, when one-third of their whole tonnage (3,000,000) had been destroyed. The ship owners were happy to claim the insurance and, until 1917 the German U-Boats treated the ships’ crews well, allowing and even helping them to escape. It was only when the treatment of Norwegian crews worsened, and the insurance companies refused to pay up any longer, that the situation was resolved.

Millais explains how, in October 1915, he and a colleague were on a ship to the Norwegian mainland when they realised that two fellow passengers were in fact very good German spies who didn‘t fit into Millais’ jokey stereotype. He managed to give them the slip by giving out misleading information, much to his friend’s confusion:

What fool business are you up to now?” quoth my friend when he came up on deck. “Well , it is just this” I replied. “Those fellows are up to no good, and if we go by the Bessheim (ship) we shall probably find ourselves in a mess. I for one am going to Bergen.” Argument is easy with normal creatures, by my friend was about to be married, and so in his case it required some very urgent reasons to make him see the point, but at last he gave in and went south by the slower route.

It turned out that the boat they were going to travel on would later be stopped by a German U-Boat captain asking for two Englishmen fitting Millais’ and his friend’s descriptions. Not finding them on board he took another Englishman captive, who was imprisoned in Germany for 6 months.

In 1916 Millais sailed north to Hammerfest, the most northern town in the world, which spends seven months in the grip of the arctic winter. Hammerfest was the central point of the main cod industry of Norway, supplying Germany with large quantities of the fish. In his book, Millais writes that, whilst the Norwegian intelligentsia and military might be pro-British

the main population of Norway,…were actively or passively pro-German... She bought nearly the whole of her fish, and her commercial travellers (all speaking Norwegian fluently) travelled everywhere on the coastline and sold their goods. Nearly everything in the shops was German…Moreover, the Germans were paying the Norwegians something like a 600 per cent advance on the price of their fish, whilst we, who only began to buy fish on a large scale in 1916, were offering only something like a 200 per cent advance…In this atmosphere of pro-Germanism one had no friends and no one to talk to. The telephone and telegraph girls were all German spies, and one had to be very careful that all messages were unintelligible to them. When the submarine difficulty began in September, they did not actually refuse to take my messages …but took good care that these messages were never delivered.

Millais explains that the further north he went the more the nature of the Norwegian changed:

They lounge about, expectorate freely and seem to know little about seamanship, the oil motor having changed all that. They do not even take the trouble to repair their rotten harness, or to caulk their boats - an atmosphere of cheap second-rateness hangs like a pall over everything they do and everything they possess. Their houses and shops are paltry, and filled with cheap German rubbish. There is little life, warmth or colour in their lives or ambitions, and only a rise of half a kroner in the price of cod rouses the smallest enthusiasm. More handsome girls are to be seen in five Minutes in a street in London or Florence than in a year in northern Europe, and severe outdoor life in drab surroundings seems to be the ruin of female charm

The Russians were supposedly defending the Norwegian coast yet didn’t seem to do so. One Russian captain, who said he had sunk two U-boats, was proven to be a liar when they resurfaced the same evening. However, that didn’t stop him receiving medals and decorations, and receiving praise in the English press.

Millais describes how several Norwegian captains, had they had asked him for information, could have avoided disaster. Yet they didn’t, happily accepting the insurance money instead, “for they well knew that the Germans would in every case safeguard the crews, even in most instances towing the ship boats close to the coast after sinking the vessels.”

However, crews from their enemies were treated differently and without care, “English, American or Romanians crews were simply cast off in their boats in the Polar sea at night….” Millais then lists the seven ships that were lost, and the English, American and Romanian crews he helped from the 2 to 26 October alone. After the 1 December 1916 Millais turned south, as the German U boats could no longer hunt. He went to Bergen where, upon his return, he found the town full of Germans. Millais avoided capture with the help of the harbourmaster and returned to Newcastle, and then home to Compton Brow.

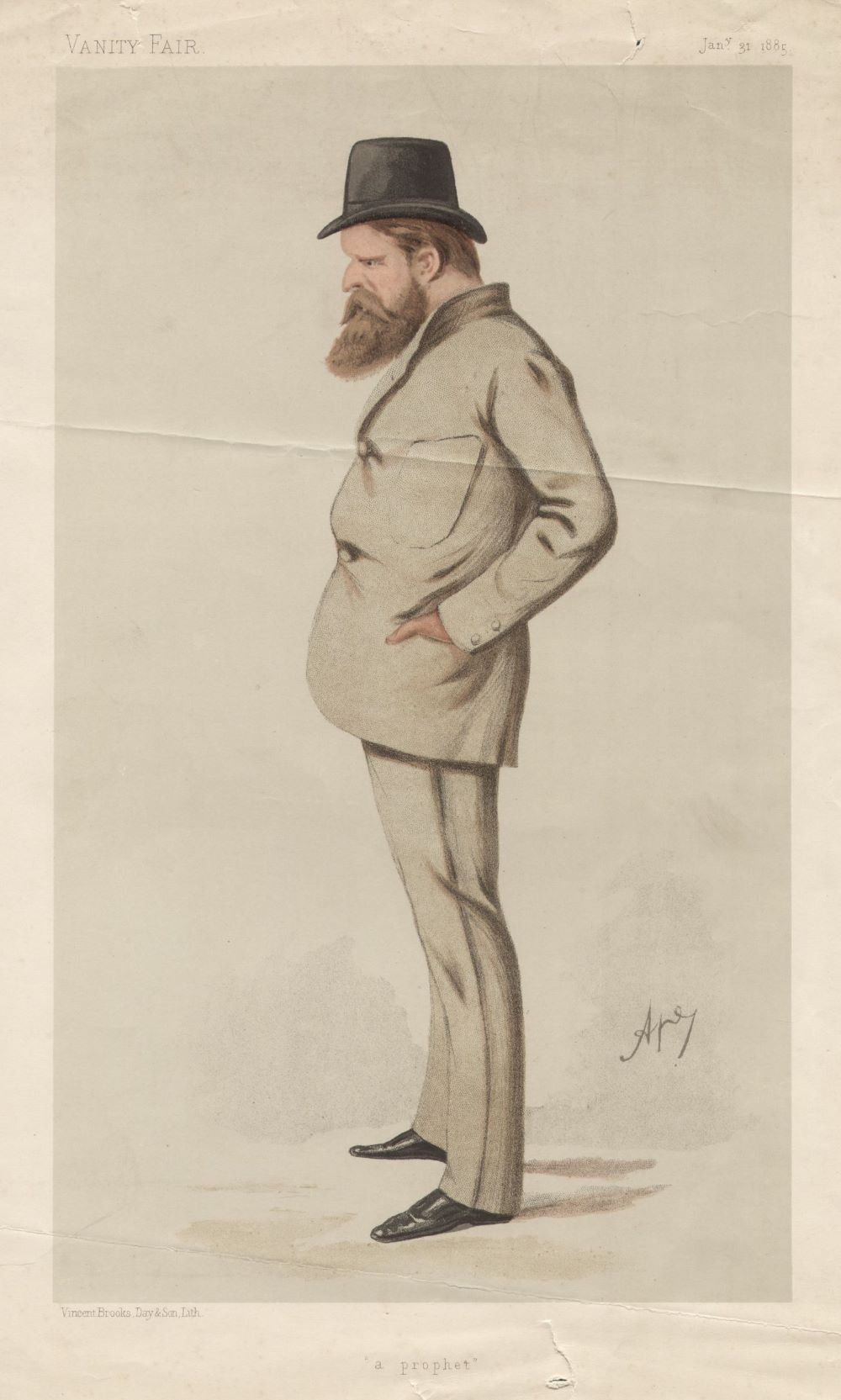

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt: Arabian explorer, horse breeder, friend to all, writer, poet and lover

Throughout the First World War 75 year old Scawen Blunt, who lived at Newbuildings in Southwater, entertained many of the leading politicians of the day, including Winston Churchill. Those that couldn‘t visit kept up extensive correspondence with Blunt. One of the correspondents was Blunt’s old flame, to whom he wrote his first published poetry, the courtesan Catherine Walters aka Skittles. Skittles' benefactors are rumoured to have included intellectuals, leaders of political parties, aristocrats and a member of the British Royal Family.

A letter dated 20 November 1914 records how well she also knew the German Kaiser who, as Crown Prince, gave her a photograph and a jeweled sunshade which she sold to raise money for the poor wounded troops. According to Blunt’s annotations to the letter, when Skittles recalls that she was “a girl” at this time, “she cannot have been less than forty”. Skittles also occasionally visited Blunt in Southwater. In March 1918, Blunt wrote:

Thank God, here is spring at last, a roaring lion it has come and with it XX (Skittles) …to spend the day and see the horses. Though deaf and partly blind XX is unconquered in talk, and gave us all the gossip of the hour though it is too piecemeal for reproduction….I sent her away happy with a basket of butter and eggs to eke out her London rations.

What we do not know, but would not be beyond probability, is whether Blunt passed any information about the Kaiser gleaned from his conversations with Skittles on to the British cabinet. Though Blunt detested the war and argued strongly against Britain’s involvement, idle chat and snippets probably flowed freely. Would this count as spying? Well, in the 1960s Keeler and Profumo affair, which involved indiscretions and became a cause-celebre, even the possibility of spying had serious ramifications for the government. Would we allow it today?

Published: 17 Jun 2020