Dominic Cummings attracted huge attention as he attended a committee recently. Imagine if a coach load left Horsham, stayed overnight and then spilt the beans to a parliamentary committee on kidnapping, drunkenness, bribery and corruption involving the Attorney General. That is what happened to the good folk of Horsham in 1847 and the report, which is over 2 inches thick, details it all in sworn statements.

The Great reform act of 1832 didn’t really reform Horsham. The number of people who could vote was still small and the power was still in the pocket of the wealthy. When a man called Fitzgerald arrived at Horsham in 1845, he paid £1,000 over the asking price for Holbrook on the understanding that he could be elected as MP. Once in place he started to do the “rubber chicken circuit” as it is called today – charitable and society events, getting known.

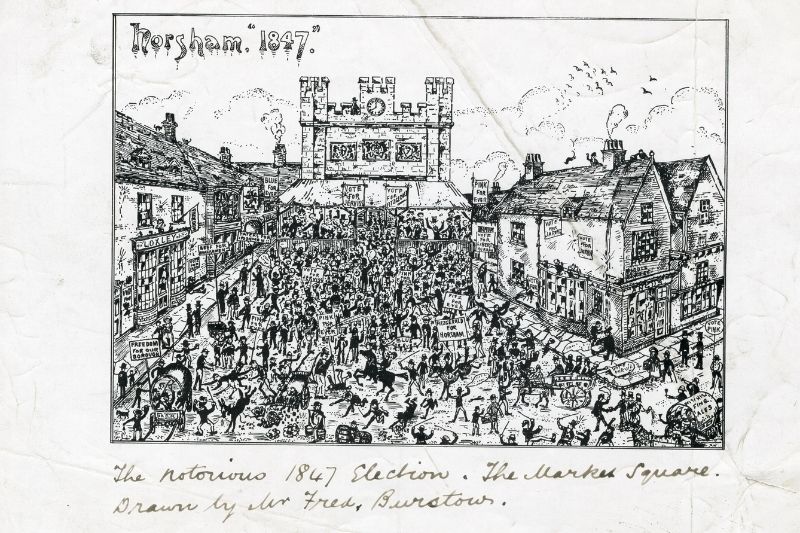

The 1847 election

When the election was called in 1847 it was Fitzgerald (depicted as an older man in the illustration here, dated 1874) against Jervis- the son of John Jervis, the attorney general. The town descended into drunken bribery, with inns and houses serving free drink to respective rosette-wearing individuals. At the election Jervis got 164 votes, Fitzgerald 155. The Parliamentary report goes into great detail concerning the drunkenness and availability of liquor in Horsham, the amount of money given as monetary bribes, buying property and, if that did not work, kidnapping of voters, before explaining how the voting habits of landlords would influence tenants.

What is clear is that, in total, 319 voted; less than 10% of Horsham’s population, so the drunken behaviour was not endemic, except with those that had the vote and chose to do so. At one event at the “Richmond Hotel” 120 people attended, along with “the candidate, his friends, supporters, voters, non-voters and riff-raff – consumed 200 bottles of wine, 40 bowls of punch, grogs and ale at a cost of £80.” Not all those that had the vote took bribes: John Seagrave, a journeyman baker, refused £50 in gold, whilst William Pannett, a part-time schoolmaster, refused £100.

For those non-electors it was impossible not to avoid the election. The printing presses of Horsham were churning out squibs: doggerel verses that parodied the popular street literature of the day, or children’s stories such as The Butterfly’s Ball. These notices were flyposted around the town and in drinking houses. In addition, at least 17 inns and public houses had blue or pink flags flying outside the doors, and children of voting parents wore ribbons.

At the election Henry Burstow was a white boy; an old ritual explained by him:

Each candidate had about twenty. Each white boy was dressed in a white round frock and carried a pole about six feet long, painted red or blue, according to the colour favoured by the candidate in whose interests he was engaged. We were paid 5s each per day, and could have as much to eat and drink as we liked. Our duties were to keep the way to the hustings clear for voters, and to make ourselves otherwise generally useful. Polling ceased punctually at 4pm.

Allegations of corruption

Immediately the result was called the election was called into account due to corruption, and Mr Fitzgerald was unseated after an investigation by the parliamentary committee.

The election was called again after the bribery in 1847. This time Jervis did not stand, but Lord Edward Howard stood in his place against Fitzgerald. Howard was not the first choice: the first was Sir Percy Florence Shelley, the only surviving son of Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley, but the election day fell on the same day as his marriage so he turned down the nomination. So the second son of the Duke of Norfolk was called upon: he consented only if he did not have to spend a penny beyond the minimum legal requirement.

This was not because he objected to bribery, but because he did not want to spend money. It was a strategy that worked well. The story is told in the diary of Rowlendson:

“1848. July 1st ...Wednesday and Thursday took place at the hustings erected on the Gaol Green the Election of a Burgess to serve in parliament for the Borough of Horsham when the Candidates where Mr Fitzgerald and Lord Edward Howard as Sir P.F. Shelley xxx?xx The Poll closed on Thursday when the number for Mr F 182 and for Lord E 115 and Lord E declared he would Petition against the return. Lord E Howard never canvassed at all nor had any Committee no Bans flags or Ribbons. Mr F had a Band from Dorking and his old flags and some of his Supporters wore their tokens”.

At the appeal Fitzgerald was unseated for corruption and Howard was elected as he had not spent a penny; there could be no suggestion of corruption or bribery. But he did not bother canvassing or doing anything; it was a non-event and, in many respects, Fitzgerald would have been the more worthy candidate because he at least showed an interest in the seat; an interest that cost him dear.

Published: 02 Jun 2021