Horsham Museum is looking at the early days of coffee drinking and the town’s first known café.

One of the great discussions of the economic impact of the pandemic has been that of its effect on coffee shops. Coffee shops that have bustled and boomed in London and other cities, and at railway stations serving millions of customers their early morning fix. Alongside those discussions went the realisation that some local coffee shops and cafés were thriving as stay at home workers went out and shopped locally rather near their normal place of work. Such conflicting stories will continue throughout the pandemic and beyond, so today Horsham Museum is looking at the early days of coffee drinking and the town’s first known café.

The 17th century saw the rise of two great drinks, coffee and chocolate. Though not as well-known as coffee shops, there were chocolate shops serving hot chocolate. It was coffee that caught the public imagination. This is partly because of the role of coffee shops in developing the news trade and stock markets as they were a meeting place for to talk and share ideas, something that is still part of their role 250 years later.

Coffee houses were a relatively new concept in drinking; a space that was not an ale house, where the beverages did not make you drunk, and that was a male preserve. Introduced into London in 1652 at the height of the puritanical Commonwealth which attacked licentious behaviour, the hot bitter black drink from Turkey proved a hit, spreading quickly through urban merchant areas.

As with anything new, it is through the copying of others that people learn. In this case, the coffee shop in Horsham would have mimicked the coffee shops in London and other towns and cities where merchants and men circulated. The drinking of coffee, the coffee house and the creation of a male space were creating a brand and a culture that was unique. The experience was such that it led to satires being written about the culture, satires which help explore how the space functioned and how people responded to it, both men and women. As a caveat, it is impossible with the documentary material we have available to know for certain if Horsham viewed the coffee shop in the same cultural way as London, but London was not alien to Horsham, Horsham was not parochial.

Before we explore the culture of the coffee shop, the matter of sex needs to be explored. Originally, in the 16th century and earlier, the coffee houses of Istanbul employed young attractive boys to serve clients coffee and sexual favours. It was reported on by travellers and explorers. It could therefore be questioned whether the male preserve of the coffee house led to a similar culture developing in London, and by extension, Horsham. The answer has to be ‘no’. All references in the late 17th and 18th century satires and descriptions of coffee houses are of men being enticed in by a flirtatious woman, or linking the coffee house to female prostitutes, though young “coffee-boys” were present. However, the coffee boy was seen as an apprentice performing the function, more akin to a “butler”, doing errands, collecting newspapers, serving coffee etc.

The very male preserve of the coffee house led to some serious concerns about the effects of coffee on men’s sexual performance, though such concerns were expressed in satire and the occasional medical survey. The most well-known satire being “The Women’s Petition Against Coffee. Representing to public Consideration the Grand Inconveniences accruing to their Sex from the Excessive Use of that Drying Enfeebling Liquor. Presented to the Right Honourable Keepers of the Liberty of Venus” (1674). The satire was full of double entendres attacking coffee for making Englishmen feeble, and that social man, the man who entered the coffee house with his endless chat and talk was impotent. The satirist accused coffee-house customers of being ‘effeminate’ because they spend their time talking, reading and pursuing their business, rather than carousing, drinking and whoring, “ that men will soon out-talk women”. This attack was riposted with, “The Mens Answer to the Womens Petition Against Coffee…”, published in the same year, 1674, which argued that the modern man, the coffee shop man, bent over backward to please women, going on the argue that coffee in fact makes men vigorous.

The culture of the coffee shop

It was in so many ways a new space and a transforming space, enabling new ideas to circulate and develop. Where else could men go to discuss, debate and read, if not the tavern or the gentleman’s home? It also allowed into the discussion those who could afford a cup of coffee, 1d, thus allowing a democratisation of discussion and debate. With this new transforming space we see the introduction of the insurance market, the Bank of England, the stock market, new forms of finance enabling the wealth of Britain to circulate, as well as the democratisation of science and the development of a literary culture.

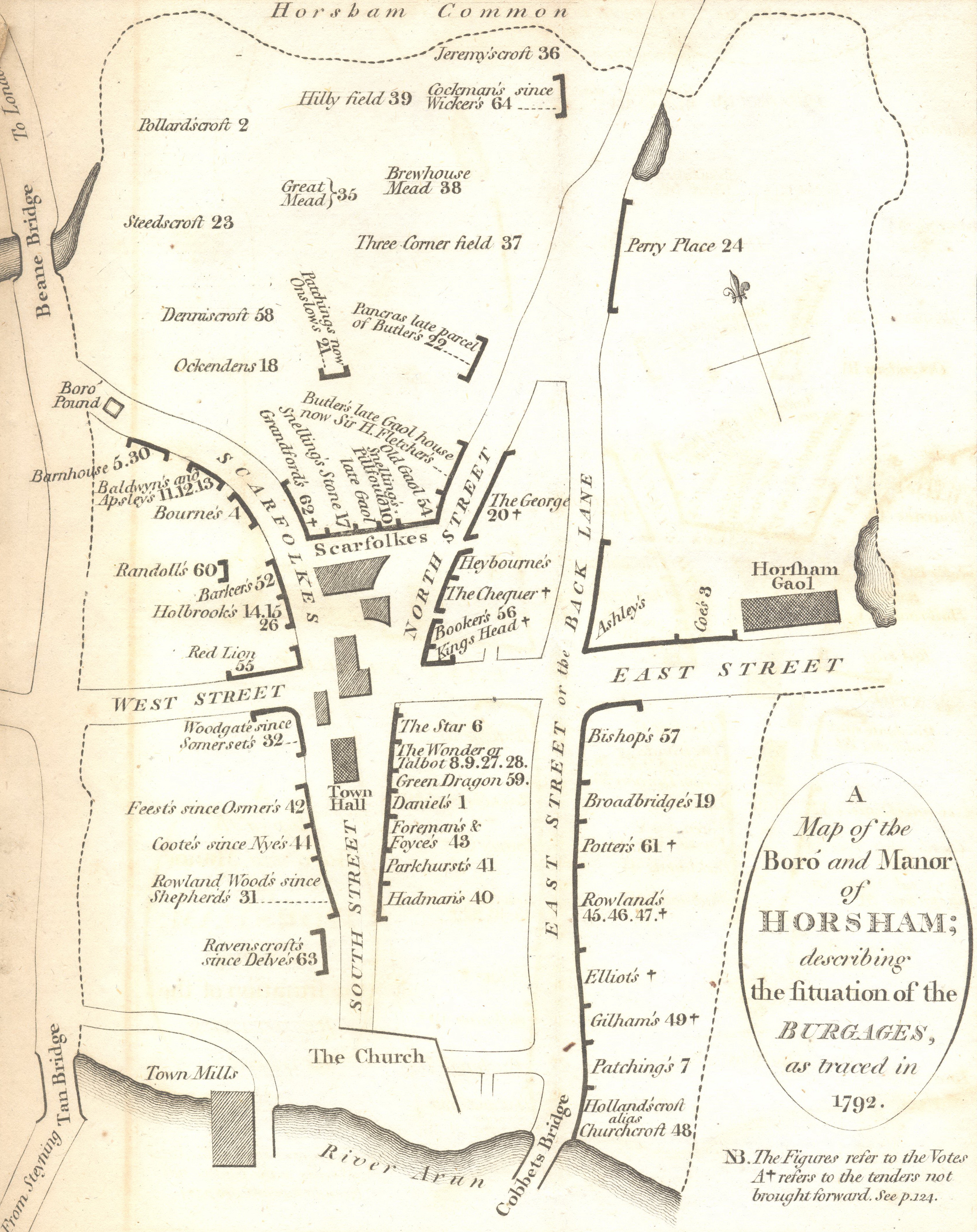

And it spread to Horsham as the probate list for The Star, date to 1701/2 in Horsham’s Market Square reveals. The innkeeper Henry Waller who, leased the large building which seemed to function as an inn and a coffee shop. It is though the room listed in the probate as “the Cooffe Rume” which concerns us. It had “one dosen of Leather Chears 4 Table 3 Arme Chears one Stolle 3 Tubes one Tonges one peare of brand Irons”, which strongly suggests “café society” had reached Horsham; a café or coffee shop with a fire, easy chairs and tables and chairs. The Kitchen had “coofee potts mille and rostar”, to roast, grind and serve the sludge-like coffee, which was drunk, dark, unfiltered and sweet. Whether we can envisage London-style coffee shops with newssheets and merchants debating the cost of trade and local and national news is open to question, but Henry Waller did have “30 pounds in the Sheare of A vessel at sea”; perhaps he was persuaded to join a joint stock venture by one of his customers?

The Star would have been located where Cafe @ No 4 is currently sited in Horsham's Market Square

Published: 30 Nov 2020