Today as Sussex is facing issues with water supplies and possible droughts, we take a look at the history of public water supplies in Horsham District.

In the past water was free. It naturally flowed in rivers, bubbled up in springs, and fell from the sky God given. Why pay for it? In fact, as the following story recounts, that attitude was prevalent for centuries, causing Horsham to have higher death rates than the big industrial cities in Victorian Britain. We take access to clean, fresh water for granted today but how it first came to Horsham is a fascinating story.

The first account of public water supply in Horsham is in 1627. It was recorded that, “…the public fountain (fons publicus) in the North Street called Comewell, is very defective for want of a curb and, a nuisance, and is to be repaired before the next Court”.

Then, in 1646, mention is made of the Parish having to pay for the repair of the Normandy well. It appears that the Borough looked after the North Street well and the Parish looked after the Normandy well. The records then stay silent for nearly 100 years, until 1742, when there is a remarkable agreement signed by William and Resta Patching stating that, “William and Resta Patching had undertaken to serve the Inhabitants of the Borough and Town with Water from and out of the River called Horsham River”.

The agreement also gave the Patchings permission to take up pavements and lay water pipes for a term of 500 years at a rent of 6d per year. One condition of this indenture was that water should be supplied free of charge to the Manor House, including water for the fountain in the “best” garden. Additionally Resta and William ran the Town Mill and also had the authority to, “erect, set up or build any Engine or Engines for conveyance of Water in the said River to the inhabitants of the Town and Borough of Horsham with rights to lay pipes through the Church Field”.

The museum has a few fragments of these wooden pipes. If fresh water was supplied, was sewage taken away? In the accounts of Horsham Gaol that were presented at the quarter sessions in 1743, there is an indication that sewage pipes were laid from the gaol at a cost of £2,700. The sewer was “sixteen inches wide and twelve inches deep, finding all material viz, lime, sand and stones”, and it appeared to have been used for draining the Carfax, as it went through the area to West Street and beyond. At the same time fresh water was supplied to the gaol via pipes from the town waterworks even though there was a spring nearby. It would appear that the town got fresh water from the river, and had its sewage taken away by charging the County.

No interest in water

In 1836 Howard Dudley, the precocious 16 year old author and illustrator of Horsham’s first History book, would write, “The water around Horsham is of a very superior quality, and extremely abundant. It is intended shortly to supply each house by means of pipes”. This may have been a proposed scheme rather than a fully-formed plan as it was another 40 years before it became a reality. However, the comment made by Dudley is interesting as the water in Horsham was very good, but the water supply was heavily polluted as much of it came from shallow wells. Some 20 years later a report showed how much contamination was actually in the Horsham water supply. Horsham well water had 49 grains impurity per gallon compared with only 2 per gallon for Glasgow. Henry Burstow also recounts the story of Ned Hall:

The waterman… Well water at Horsham, too, was very hard and most people used to save all the rain water they could for washing purposes, &c. With his pony cart and barrel old Hall could always in summer time do a good trade in water, which he used to fetch from the river, selling it at a half-penny per bucketful, and with a wooden trough, fitted behind the barrel, watering the streets, charging 1d per time for watering the road in front of a house

Victorian “Do Gooding” has no effect

In 1858 the Local Government Act was passed. The following year Robert Henry Hurst Jr. tried to persuade the town of Horsham to adopt the act but the final vote was 160 to 6 against. Then, in 1862, scarlet fever struck and through the Literary and Scientific Institution Robert Henry Hurst made it known how much worse off Horsham was in its death rate than neighbouring Sussex towns. He formed an action committee which issued a broadsheet headed “Health of Horsham” which showed that the drains were defective, the cellars were infested with rats and sewage, and that the wells were between 14 and 24 feet deep and therefore susceptible to pollution. The water was so bad that when it was heated a greasy film lay on top like scum and smelt appalling.

The total deaths per thousand were 25 for Horsham, 16 in the rural districts and 24 in the country as a whole. The solution was to create deep main sewers and a find a pure water supply. What was even more shocking, during the outbreak of scarlet fever Horsham’s death rate was 15%, when 10 % was considered high nationally. The failure of quasi-local government committees to make the necessary changes possibly encouraged Robert Hurst to ask private companies to invest in the town infrastructure and reap the benefits

On 31st August 1865 the first Ordinary General Meeting of the Horsham Waterworks Company was held at the Literary Institution. The prospectus was issued to raise £5,000 on the basis that:

an experimental Well has been sunk upon Land in Park Terrace East, Horsham, belonging to Mr Michell, with a view of testing the supply …The abundance of the supply, obtained at a depth of only 75 feet, has exceeded the most sanguine anticipation of the promoters of the Experimental Well, and has been secured at a comparatively trifling cost” it goes on to state that “the water from the main spring enters the Well at a rate exceeding 60,000 gallons a day. It has also been ascertained that, notwithstanding the heavy rain-fall of the recent winter, no land springs have found their way into the Well.

In 1868 Dorothea Hurst, the sister of Robert, wrote in her “History of Horsham” about the wells of the town:

There is a considerable variety in the water of the springs in this parish, which ranges from very hard to very soft; some few have a brackish taste, others are more or less impregnated with iron…In general, however, the quality of the water is considered good, and some of the wells are remarkably pure and unfailing. This observation particularly applies to an ancient well, called…”The Normandy Well”….The Normandy Well is open and runs partly under one of the houses; it is only about four feet in depth, and yet in the longest drought the water always stands up sufficiently high to allow a pail to be dipped into it. It has been the custom to use the water from this well for the baptisms in the church

Dorothea then goes on to discuss the new water supply and offers a different perspective on the comments made by her brother. According to her writings, the real reason for the establishment of a new water company was not the poor quality and contaminated water, but was actually driven by the effects of a couple of dry seasons.

Most of the old wells are from ten to fifty feet in depth, twenty-five being perhaps the average; but the recent dry seasons, especially those of 1864 and 1865, have proved that the supply at this depth is not sufficient for the existing needs of the town. To remedy this defect a company has sunk a well of seventy-five feet, and a large reservoir has been formed a quarter of a mile on the eastern side of the town.

Victorian zeal takes over

On 12th April 1875 a public meeting was held with a resolution to adopt the Local Government Act. The Public Health Act of 1875 forced the issue leaving little room for manoeuvre. In May a poll was held to confirm this decision and 518 voted for it, 222 against. Work could now begin on sorting out the town’s problematic water and sewage.

The local government bought out the Water Company for £7,000 bringing it under their control. In May 1879 Horsham’s drainage system was completed at a cost of £13,560, almost £6,000 above the original estimate of £7,590. In 1882 Kelley’s Directory states that, “a large reservoir…in the high lying ground near the union house, for the constant supply of the district” was to be constructed. This became the Star Inn Reservoir, built near the Workhouse in Crawley Road, which opened in 1883.

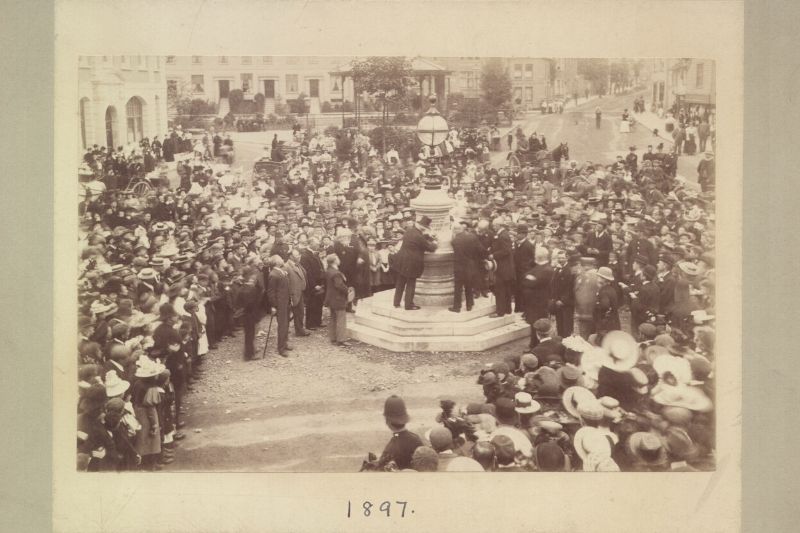

The possibility of fresh clean drinking water led the town to create a drinking fountain in honour of Queen Victoria. As we take drinking water for granted we do not understand the pride felt by the people of Horsham for the fountain, so it now stands largely ignored on Charts Way rather than having pride of place in the Carfax. Photographs from the Museum’s collection show the pride the town took in the feature at the time.

By the end of the century Horsham had apparently resolved the issue of unsafe drinking water and sewage contamination that was first brought to public attention in 1850s. It now had a public drinking fountain that tourists as well as Horsham folk could be proud to drink from, and a fountain that praised and paid homage to Queen Victoria, a Queen who had overseen the transformation of Britain’s infrastructure including its water supply.

Before we finish the century, in 1898 when the Anchor Hotel was being rebuilt, an event occurred that reminded people of the medieval wells in the town. On Saturday 19th March it was reported that:

during the work of making up the roadway in the Market Square the steam roller and its driver had a narrow escape from an accident. While running the roller backwards the driver felt the ground sinking beneath him. He at once put on full steam, and on feeling solid ground again, stopped dead. Meanwhile, the ground between the front & back wheels of the roller fell in, disclosing a large well about Twenty two feet deep and with Nine feet six inches of water in it. The roller was soon got out of its awkward position, and on the following Monday the well was pumped dry and then filled in

We know about this incident because a fine illuminated testimonial recounting Mr Henry Penfold’s endeavour was presented to him by Horsham Urban district Council “as a mark of their appreciation of the presence of mind displayed by him”.

Published: 12 Jun 2020