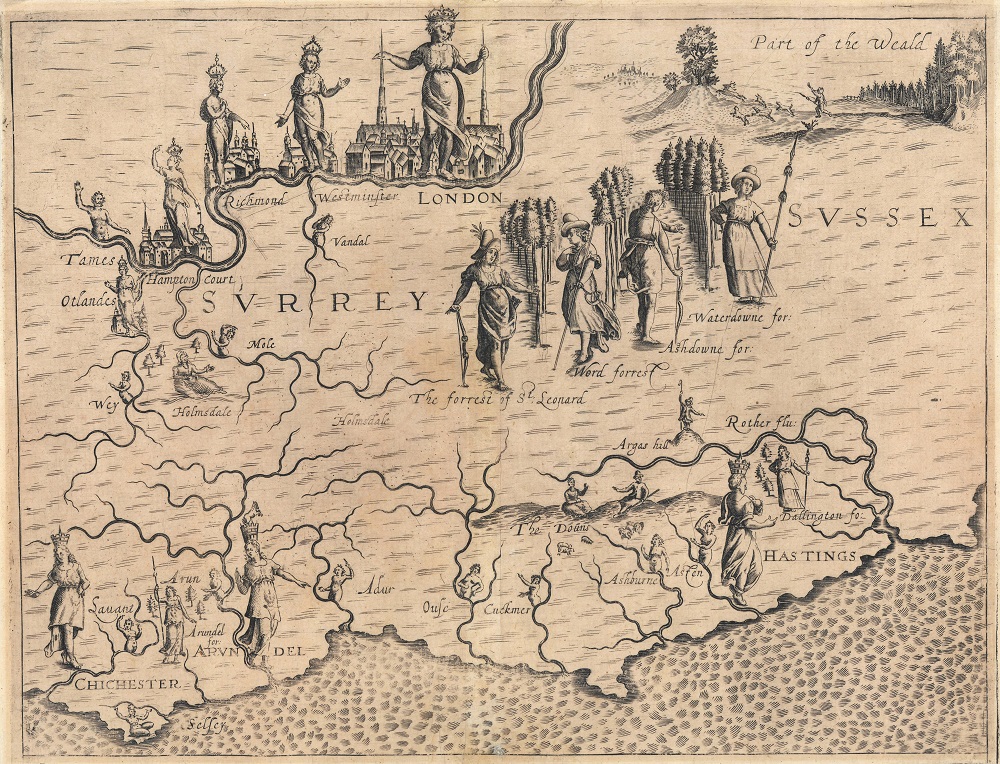

Horsham Museum & Art Gallery has just acquired a very rare copy of the map to be part of its new gallery on Horsham District in the medieval and Tudor periods.

Maps are an amazing creation of the mind for they show what a 3D landscape looks like in 2D. They aim to be accurate; otherwise, what is the point of them? It is for this reason that one of the most remarkable maps of the southeast, including St Leonard’s Forest, was ignored for centuries. Yet the map is a powerful portrayal of the landscape created in the age of Shakespeare.

Michael Drayton

In 1612 Michael Drayton, poet and friend of Shakespeare, wrote and published an epic poem on his beloved Britain, Poly-Olbion or A Chorographicall Description of Tracts, Rivers, Mountaines, Forests, and other Parts of this renowned Isle of Great Britaine. The poem describes the countryside, local myths and incorporates Arthurian legends in an era when such tales were part of everyday folklore. To add depth and understanding to the poem, John Selden, born at Tarring near Worthing and linked through the Archbishop of Canterbury with the Bishopric in Horsham, wrote extensive notes or “illustrations”. The popularity of the poem was such that it was extended and republished 10 years later. The poem is a remarkable tour-de force as it gives a voice to natural features, with rivers becoming narrators for example. Just as Disney today humanises animals to get over messages, so Drayton did the same over 400 years ago. We may think such an idea odd, but many cultures have Gods of natural occurrences, and beliefs in sea monsters was common at that time. Such ideas turn natural features into human form.

Alongside the poem Drayton commissioned William Hole, a leading engraver, to create 30 maps to give visual form to his poetic narration. Horsham Museum has just acquired a map that portrays St Leonard’s Forest as a wood nymph holding a bow, identifying it as a hunting park. She stands next to three other wood nymphs portraying woodlands that form part of today’s High Weald forest ridge; Broadwater (Water-downe), Ashdown (Ash-downe), and Worth (Whord).

Some 33 years before these maps were created, in 1579 William Saxton published his celebrated Atlas of England and Wales, and in 1611 John Speed his Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain. These maps were what we expect maps to be, they showed where places were, locating villages and towns in the county and countryside. For that reason the maps from Poly-Olbion have been ignored for centuries, seen as curios. They were neither given credit by map collectors or by those who admire the poetic genius of Drayton, so were never included in reprints of Drayton’s work. It wasn’t until the middle of the 20th century that people realised that the maps were an integral part of understanding the poem, giving visual form to the complex verse.

Yet today, as we seek to live in partnership with our natural world, the idea of giving voice to nature has never been stronger. Now Drayton’s poem is inspiring new readers, and Hole’s maps, with their portrayal of those features now better understood, is inspiring artists. In 1614 a pamphlet was published about finding a serpent that was not a dragon, two weeks later a lost pamphlet described how the serpent died. That imagery and legend came to represent the forest of St Leonard’s. Yet more powerful and more meaningful in the mind of early 17th century Sussex was the wood nymph holding a bow, and the lines from Drayton’s poem describing the devastation of the woodland that occurred at this time. Though Drayton put it down to the iron industry and charcoal burning, research now shows such industry maintained the woodland and that the loss of woodland was down to political pressures.

As mentioned at the start, maps are remarkable creations of the mind in showing the 3D world 2 dimensionally. Holes’ map is equally remarkable because it sets out the ideas that people felt about a place in map form and as a representation. It helps to map out the mind of early 17th century people.

Drayton's Poem

To seaward, from the seat where first our song begun,

Exhaled to the south by the ascending sun,

Four stately wood nymphs stand on the Sussexian ground,

Great Andredsweld’s sometime: who, when she did abound,

In circuit and in growth, all other quite suppressed:

But in her wane of pride, as she in strength decreased,

Her nymphs assumed them names, each one to her delight.

As, Water-down, so called of her depressed site:

And Ash-Down, of those Trees that most in her do growe,

Set higher to the downs, as th’other standeth low.

Saint Leonards, of the seat by which she next is placed,

And Whord that with the like delighteth to be graced.

These forests as I say, the daughters of the Weald

(That in their heavy breasts, had long their griefs concealed)

Foreseeing, their decay each hour so fast came on,

Under the axe’s stroke, fetched many a grievous groan,

When as the anvil’s weight, and hammer’s dreadful sound,

Even rent the hollow woods, and shook the queachy ground.

So that the trembling nymphs, oppressed through ghastly fear,

Ran madding to the downs, with loose dishevelled hair.

The sylvans that about the neighbouring woods did dwell,

Both in the tufty frith and in the mossy fell,

Forsook their gloomy bowers, and wandered far abroad,

Expelled their quiet seats, and place of their abode,

When labouring carts they saw to hold their daily trade,

Where they in summer wont to sport them in the shade.

Could we, say they, suppose, that any would us cherish,

Which suffer (every day) the holiest things to perish?

Or to our daily want to minister supply?

These iron times breed none, that mind posterity.

Tis but in vain to tell, what we before have been,

Or changes of the world, that we in time have seen;

When, not devising how to spend our wealth with waste,

We to the savage swine, let fall our larding mast.

But now, alas, our selves we have not to sustain,

Nor can our tops suffice to shield our roots from rain.

Jove’s oak, the warlike ash, veined elm, the softer beech,

Short hazel, maple plain, light asp, the bending wych,

Tough holly, and smooth birch, must altogether burn:

What should the builder serve, supplies the forger’s turn;

When under public good, base private gain takes hold,

And we poor woeful woods, to ruin lastly sold.

Published: 19 Jan 2021